“Sab marr jaayenge, sirf Trivedi bachega.”That line from the OTT series ‘Sacred Games’ has lingered in India’s pop culture as shorthand for ruthless consolidation. But in China, it captures the logic now governing PLA’s top military ranks.Driving the news

- Over the weekend, President

Xi Jinping ordered investigations into GenZhang Youxia and Gen. Liu Zhenli, the last heavyweight commanders still standing at the summit of the People’s Liberation Army. - The move leaves Xi in sole operational control of the armed forces through the Central Military Commission, the most powerful institution in the Chinese political system. The PLA’s official newspaper went further, accusing the generals of undermining Xi’s authority and damaging the party’s “absolute leadership over the military,” according to reporting by the FT.

- This was not just another corruption case. It was a declaration that, inside the PLA, survival now depends on one thing above all else: unquestioned loyalty to Xi.

Why it mattersIn China, the gun decides everything.The Communist Party came to power through civil war, and it has never forgotten Mao Zedong’s dictum that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” Control of the military is therefore existential. Lose it, and the party – and the leader – risk everything.That is why Xi’s latest purge matters far beyond Beijing gossip or personnel reshuffles. By hollowing out the CMC and sidelining even his closest allies, Xi has eliminated alternative power centers inside the only institution in China that has ever successfully challenged top leaders.Dennis Wilder, a former CIA China analyst, told the Financial Times that the PLA is “the only organisation in China that has a history of defying party leaders,” citing past confrontations under Mao. With Xi widely expected to seek a fourth term at the Communist Party congress in 2027, locking down the military now reduces the risk of elite resistance later.The purges also intersect with Xi’s external ambitions.According to US and Taiwanese officials, Xi has ordered the PLA to be ready to take Taiwan by force by 2027. That timeline overlaps with both the centenary of the PLA and the start of Xi’s potential fourth term. Symbolically and politically, Xi wants a military he trusts before either milestone arrives.

Zoom in: Loyalty is not enoughAccording to a WSJ report, Gen Zhang Youxia is accused of leaking information about China’s nuclear weapons programmes to the US. He is also accused of taking bribes for promotions.But the most obvious indication of Xi’s thinking is the official wording used against Zhang Youxia and Liu Zhenli.China’s defense ministry said the two were being investigated for “serious discipline violations and violations of the law,” standard Communist Party code for corruption. But the PLA Daily editorial went much further, accusing them of trampling on the “chairman responsibility system” – the doctrine that centralizes all military authority in Xi’s hands as CMC chairman.One of the most confusing aspects of the recent purges is that many of the fallen were once seen as Xi loyalists. Zhang survived earlier waves of anti-corruption probes, even after running arms procurement systems notorious for kickbacks. His continued rise suggested trust.Yet loyalty, in Xi’s system, has an expiration date.As Lyle Morris of the Asia Society Policy Institute told the FT, references to violations of the chairman responsibility system suggest that Zhang had accumulated influence independent of Xi himself. In other words, he may not have opposed Xi-but he may have become too powerful.This distinction matters. Xi does not merely want obedience; he wants dependency. Any senior figure who commands personal loyalty, institutional leverage, or factional backing becomes a latent risk, regardless of past service.Between the linesWhat makes Zhang’s downfall especially striking is who he was.Zhang Youxia was no marginal figure. He was a combat veteran who fought in China’s 1979 war with Vietnam, one of the few senior officers with real battlefield experience. He was also a “princeling,” the son of a revolutionary elder who fought alongside Xi’s father in the civil war. For years, analysts described him as Xi’s most trusted military ally.That is precisely why his purge matters.

Much like a Mafia don, Xi has shown that he considers even his associates to be disposable. More important, the staggering political casualties reflect that he is losing patience with his military rather than his control over it.

An article in Foreign Affairs

The WSJ described Zhang’s investigation as the biggest military shake-up since the fallout from the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. By turning on a confidant, Xi is sending a message that no one – not even those with revolutionary bloodlines or personal ties – is indispensable.James Char of Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies told the FT that Zhang’s fall also reflects factional balancing. The “Shaanxi Gang” linked to Zhang and the rival “Fujian Clique” associated with earlier purges were both power blocs inside the CMC. By cutting down leaders from both sides, Xi ensures no faction grows strong enough to challenge him.There is also a historical echoThe NYT, in an August article, argued that Xi’s purges follow the logic of Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong, where loyalists are repeatedly culled to prevent paranoia from becoming reality. Stephen Kotkin, a Stalin biographer, told the NYT that authoritarian regimes often target their own supporters because loyalty does not eliminate independent interests.In that sense, Xi’s purges say less about immediate threats and more about structural anxiety. Governing a vast system like China’s – with a sprawling military-industrial complex and no independent civilian oversight – means constantly fearing what you cannot see.Purges become a method of information gathering as much as punishment.Loyalty, in this system, is not a shield. It is a temporary condition.

.

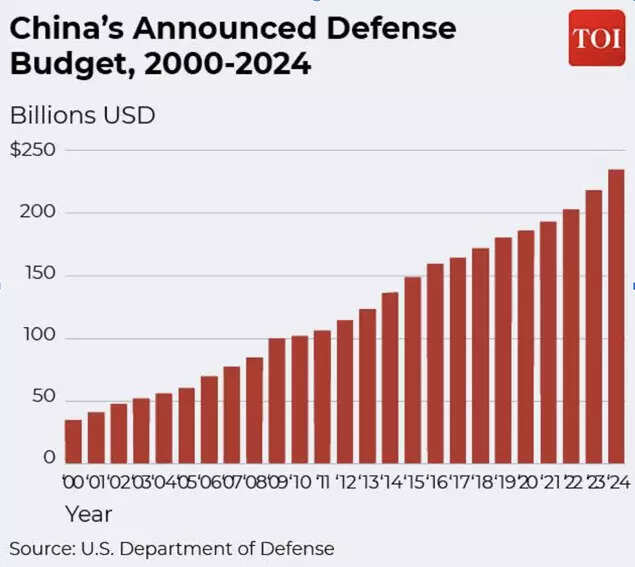

The big pictureXi’s assault on the PLA did not begin this year.Since taking power in 2012, he has used purges, restructurings, and ideological campaigns to remake the military into what he calls a force that can “fight and win wars.” Along the way, dozens of generals have been removed, two former defense ministers expelled, and entire branches – including the Rocket Force that oversees China’s nuclear arsenal – shaken by investigations.Foreign Affairs analysts Jonathan Czin and John Culver argue that two goals drive Xi’s unforgiving management style: ensuring the military is thoroughly politicized and ensuring it can fight modern wars, potentially against the US.

“This move is unprecedented in the history of the Chinese military and represents the total annihilation of the high command.”

Christopher Johnson, head of China Strategies Group, to WSJ

Those goals often clash. As the PLA modernizes, it becomes more professional, more technical, and more insular. That professionalism can drift toward political neutrality – a trait admired in democracies but viewed with suspicion in Leninist systems.Xi’s answer has been relentless churn. Promotions and purges keep officers dependent on him personally. Political commissars and loyalty campaigns remind commanders that their first duty is to the party, not to battlefield effectiveness alone.The result is a military that is simultaneously more advanced – and more fearful.Xi’s personal biography also matters.Unlike his two immediate predecessors, Xi grew up steeped in revolutionary mythology and military politics. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was purged, rehabilitated, and purged again over decades. Loyalty to the party survived personal suffering – a lesson Xi appears to have internalized.That background helps explain why Xi views hardship among elites as cleansing rather than destabilizing. Senior officers living with uncertainty, in his view, are less likely to form independent networks and more likely to seek guidance from the top.Foreign Affairs described this as Xi’s obsession with confidence – not just his own, but his confidence that the PLA will act when ordered, whether against Taiwan or domestic unrest.

.

What’s nextTwo questions now dominate Beijing watching.First, appointments. Xi cannot leave the CMC hollowed out indefinitely. Who he elevates – younger officers, political commissars, or technocratic managers – will signal whether he prioritizes ideological reliability or operational competence.Second, tempo. Ja Ian Chong told the FT that one way to judge the disruption caused by Zhang’s arrest is to watch for delays in key meetings or changes to the official agenda in coming weeks. Silence, in China, is often more revealing than statements.

Xi has reached the point where he no longer needs Zhang, who has protected him and pushed through historic reforms of the PLA, but is now perceived to be a rival and threat to Xi’s absolute grasp on power.

Drew Thompson, a China expert to Bloomberg

One thing seems certain: The purges are not ending.As the PLA approaches its centenary and Xi approaches another term, the incentive to eliminate uncertainty only grows. Like the ‘Sacred Games’ line that frames this moment, the message inside China’s military is stark: survival is temporary, power is singular, and in the end, only one man is meant to remain standing.Xi’s Sacred Games are still underway – and the chairman intends to win.