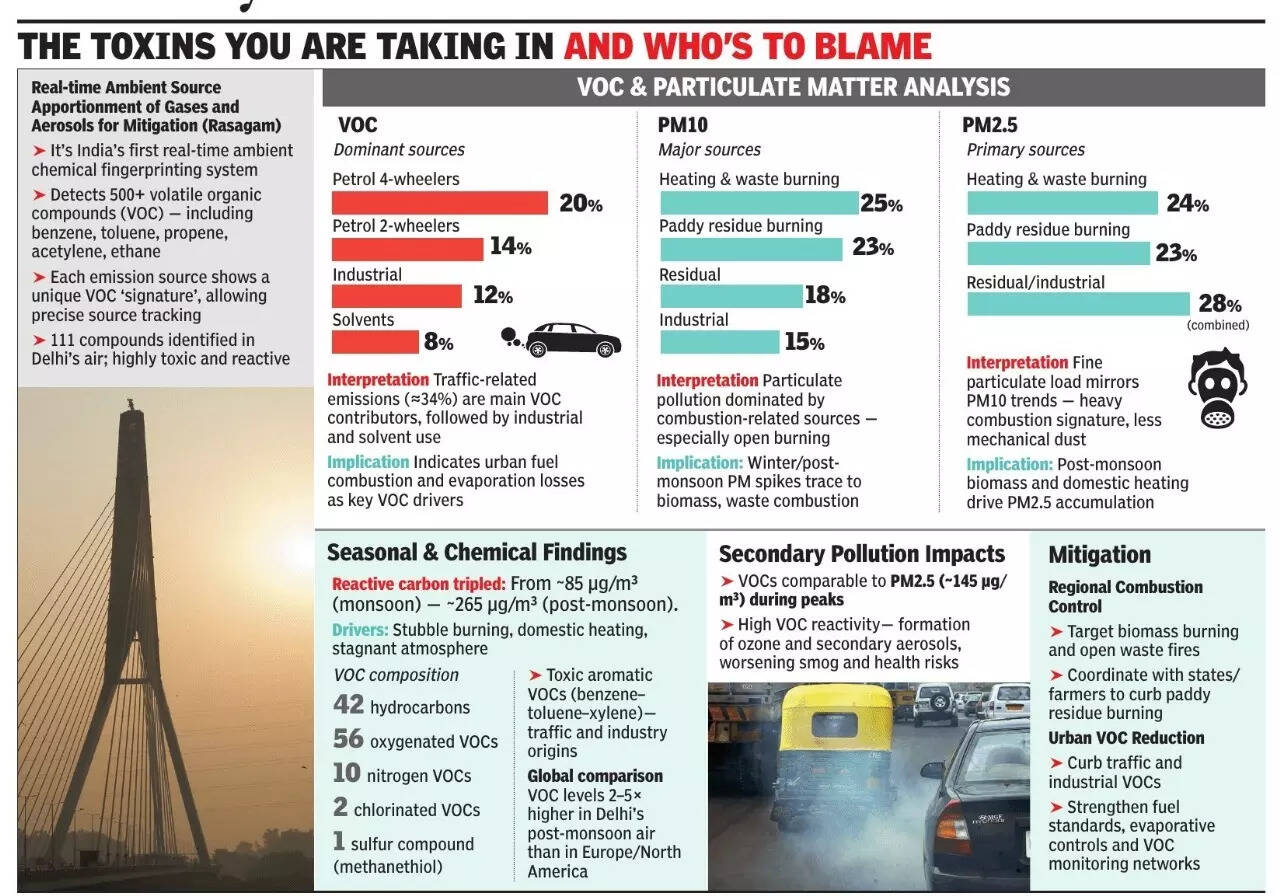

NEW DELHI: Open fires of all sorts – waste, crop stubble, cooking etc – account for over 50% of particulate matter (PM) pollution in Delhi. The transport sector, although not a major source of PM, accounts for a big proportion of carcinogenic and toxic gases like benzene, according to scientists at IISER Mohali, IITM Pune and IMD.The year-long study used latest pollution-fingerprinting technology to identify emission sources using their chemical signatures and quantify their contribution to the city’s ambient pollution.

What makes air you breathe thick & what makes it toxic Researchers used instruments capable of identifying 111 different types of VOCs that come from sources such as burning waste, fuel combustion, solvents and industrial emissions. Alongside, the scientists tracked PM10 and PM2.5 — tiny dust and soot particles that make Delhi’s air visibly hazy — as well as specific chemical “markers” that indicate the source of pollutants such as acetonitrile which point to biomass burning.

The project, called RASAGAM — Real-time Ambient Source Apportionment of Gases and Aerosols for Mitigation, was sanctioned in 2022 by Union earth sciences ministry. The data collected during the study was processed through advanced computer models that separate overlapping pollution “fingerprints”. This enables researchers to trace pollution to its exact source — whether from the burning of plastic, garbage, leaves, crop stubble, vehicular exhaust or even industrial vapours and dust.“The technology allowed us to trace pollution to its exact source,” explained Vinayak Sinha from IISER Mohali, one of the lead authors of the study.The first two peer-reviewed papers from RASAGAM, published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics in mid-2024, reveal a striking divide between what makes Delhi’s air thick and what makes it toxic. During the post-monsoon period, which typically brings the city’s worst smog, biomass burning emerged as the dominant source of particulate matter. Open burning of paddy stubble across the northwestern Indo-Gangetic Plain contributed roughly one-fourth of Delhi’s PM10 and PM2.5 levels, while waste and residential burning added a similar share.Together, these open-fire sources made up over half of Delhi’s total particulate pollution, explaining why air-quality levels hit “severe” in Oct and Nov each year. These weeks also coincide with low wind speeds, cooler temperatures, and a shallow boundary layer — conditions that trap pollutants close to the ground, turning the capital into a suffocating gas chamber.But when researchers shifted focus to VOCs, the picture changed completely. The transport and industrial sectors dominated this category. Petrol-driven cars alone accounted for about 20% of VOC mass, 25% of ozone formation potential, and nearly onethird of the potential to form new fine particles. Two-wheelers, small industrial units, and other vehicle types added large shares as well. Overall, the transport sector contributed more than 40% of Delhi’s total VOCs, while stubble burning made up only around 6%.The composition of these VOCs is deeply concerning. Delhi’s air was found to contain extremely high concentrations of benzene, toluene and xylene — toxic aromatic hydrocarbons that are known to cause cancer and respiratory diseases. In fact, the study found that these levels were several times higher than those recorded in major European or North American cities. The researchers also detected previously unreported or rarely seen chemicals, including methanethiol, dichlorobenzenes, and even C6 amides — the last of which were detected in the atmosphere for the first time anywhere in the world. These compounds can react and shift between gaseous and particle phases, making the air even more chemically reactive.This means that Delhi’s pollution problem isn’t just about dust or smoke. It’s about complex chemical reactions happening in the air every day, producing new harmful compounds that keep pollution levels high even when visible smog fades. “VOCs are not monitored anywhere in India, even though traffic is a major source of these toxic gases,” said Sinha. “If we can control open fires of all kinds and improve waste handling, it can make a major impact on Delhi’s air.”The RASAGAM studies also highlighted errors in existing pollution databases. Many official emission inventories overestimate pollution from residential biofuels but underestimate vehicular and industrial VOC emissions. This leads to policies that target the wrong sources or miss key contributors entirely.While newer BS-VI standards have cut tailpipe exhausts, vehicles still emit particulate matter through road dust, brake wear, and tyre wear —sources that are not regulated but contribute significantly to urban PM levels. “Post-2020 vehicles are cleaner, but Delhi still has a large commercial CNG fleet and heavy-duty vehicles that generate non-exhaust emissions. Whereas, heavyduty diesel vehicles are now strictly regulated and bypass the city,” Sinha added.The message from the studies is clear — Delhi’s air-quality strategy must differentiate between visible pollution and chemical toxicity. To reduce the thick smog that blankets the city in winter, regional coordination is key — especially with neighbouring states — to cut down stubble burning and open waste fires. Better solid waste management, cleaner household fuels and enforcement against backyard burning can make a big difference to particulate levels.But tackling the invisible and more dangerous chemical smog requires a different approach. Delhi needs stricter control of vehicular and industrial emissions, regular monitoring of VOCs — which is not happening anywhere in India and tighter checks on fuel evaporation, refinery leaks and solvent use.In short, Delhi’s pollution has two faces — one that you can see and one that you can’t. The visible haze comes largely from open fires, while the invisible cloud of reactive and toxic gases is driven by vehicles and industries.