In a recently released statement, the Federation of Resident Doctors’ Association India (FORDA), an umbrella body representing resident doctors across government hospitals, questioned whether NEET PG 2025 should be read as an isolated examination failure or as an institutional collapse unfolding over months.“NEET PG 2025 will be remembered as the year an institution betrayed its mandate,” the association said, listing opacity, denial of answer keys, arbitrary disqualifications, centre misallocation, delayed counselling, and finally, zero and negative qualifying cut-offs.The trigger for this latest escalation is the National Board of Examinations in Medical Sciences (NBEMS) decision to sharply lower Round 3 qualifying percentiles for NEET PG 2025. According to the NBEMS, the General and Economically Weaker Sections cutoff was reduced to the 7th percentile, equivalent to a score of 103 out of 800. For Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, and Other Backward Classes, the qualifying percentile was reduced to zero, translating to a revised cutoff score of minus 40.FORDA described the outcome straight. “This isn’t admission; it’s a lottery,” the statement said, arguing that eligibility had been decoupled from performance.

A crisis that did not begin with cut-offs

The Round 3 cut-off revision came at the end of a sequence that FORDA traces back to March 2025.In March, NBEMS announced a two-shift examination format for NEET PG, citing logistical constraints. The rationale, FORDA said, was never fully explained. “Two shifts in a single day create vastly different question difficulty levels,” the press release mentioned, while the normalisation formula meant to equalise outcomes was not disclosed.Aspirants, the association said, were “not asking for favours”. They were asking for fairness and transparency. “NBEMS refused both.”Legal challenges followed. In May 2025, petitions were filed in the Supreme Court questioning the two-shift format and the absence of transparency in the normalisation process. On May 29 and 30, the Court held that two-shift examinations were “arbitrary” and “unreliable” for high-stakes PG medical admissions, and that applying undisclosed normalisation methods across shifts posed unacceptable risks to merit-based selection.The ruling, however, came with consequences. To accommodate single-shift logistics across nearly 900 centres nationwide, NBEMS postponed the examination from June 15 to August 3, 2025. FORDA described this delay as compounding uncertainty, career stagnation, and financial strain for thousands of candidates.

Answers withheld, outcomes disputed

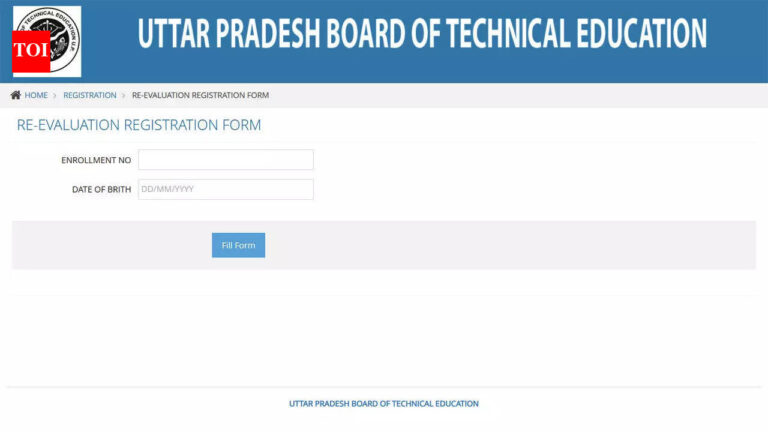

After the NEET PG exam held on August 3, 2025, aspirants waited for provisional answer keys that never came. NBEMS provided no window to challenge responses. According to FORDA, some of the 22 candidates later disqualified for malpractice “may have been trapped by flawed keys that were never disclosed.”Centre allocation added another layer of strain. Candidates from northern states were assigned centres in Chennai, while southern candidates were sent to Delhi. FORDA estimates travel costs between Rs 75,000 and Rs 1,00,000 for an examination that already cost Rs 4,250 in fees.The press release documents the cumulative effect. “Three months of uncertainty, anxiety, and lost wages,” it states, adding that women candidates faced safety concerns and economically weaker candidates struggled with accommodation and travel expenses.Results were declared on August 19, 2025, weeks after the examination. Confusion followed. Twenty-two disqualifications were announced with no appeal mechanism. “No transparency,” the association said. “Families celebrated. Then heartbreak.”

Counselling paralysis and hospital impact

By September 2025, the problem had moved beyond aspirants. Counselling that should have concluded within weeks extended for more than 110 days. Hospitals reported staff shortages. Diagnostic delays followed.“Medical seats remained vacant. Hospitals struggled with staff shortages. Patients faced diagnostic delays,” the FORDA statement said.Aspirants could not plan relocations, hospitals could not finalise rosters, PG training did not begin on schedule, and the system stalled without explanation.NBEMS later justified the cut-off reduction by citing vacant seats. According to sources quoted by ANI on January 14, over 18,000 PG seats remained unfilled after Round 2 counselling across government and private medical colleges.“These seats are vital for expanding India’s pool of trained medical specialists,” sources told ANI. Leaving them vacant, they argued, undermined healthcare delivery.FORDA completely rejects this framing. “Filling vacancies is not the same as surrendering standards,” the association said. It argues that delays, mismanagement, and opaque processes created the vacancies in the first place.

Merit diluted, trust eroded

In a letter to Union Health Minister Jagat Prakash Nadda, FORDA also urged the Centre earlier to withdraw the decision to reduce cut-off scores.“This unprecedented move undermines the sanctity of a merit-based selection process,” the letter said. “It devalues the rigorous preparation of lakhs of aspiring doctors and poses a grave threat to the credibility of the medical profession in the eyes of the common public.”The association warned that lowering cut-offs without explanation or consultation “demoralises toppers” and risks patient care outcomes.It also alleged that the move disproportionately benefits private medical colleges. “This slash favours private medical colleges by filling seats with lower-scoring candidates at exorbitant fees,” the letter said, “prioritising institutional profits over student welfare.”The Federation of All India Medical Association shared the same concern, warning that allowing candidates with negative scores to qualify would “erode public trust” and trigger nationwide protests if the notification was not withdrawn.

A system exposed, not corrected

All NEET PG candidates are qualified doctors who have completed Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degrees and internships. The dispute is not about entry-level competence. It is about whether PG specialisation is still governed by transparent, predictable standards.FORDA has called for a high-level committee comprising the National Medical Commission (NMC), the NBEMS, and resident doctor representatives to review cut-off policies and examination governance.What remains unresolved is whether the response to vacant seats will address the reasons they remained vacant, or simply redefine eligibility until numbers fit. The question NEET PG now faces is not only about admissions, but about whether confidence in the system can be restored once merit becomes negotiable.