Progress in education often signals broader social gains. In Delhi, the latest government report, Women and Men in Delhi – 2025, released by the Directorate of Economics and Statistics, shows women steering the city’s education landscape. They are entering classrooms as students and teachers in greater numbers than before. Yet this rise in learning does not extend into the labour market. Women continue to remain largely absent from paid work in the city, despite steady advances in schooling and higher education.

Women anchor the education sector

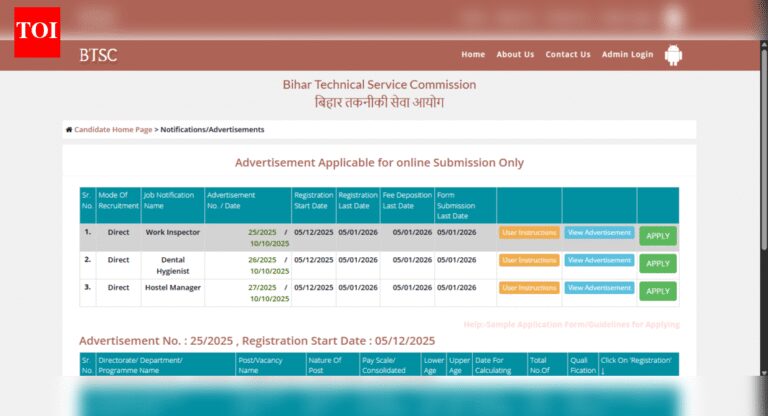

According to the report, the number of women teaching in Delhi has grown steadily across all school levels. At the primary stage, there were 415 female teachers for every 100 male teachers in 2024 to 25, up from 363 in 2012 to 13. At the upper primary stage, the ratio rose from 214 to 261 during the same period. At the higher secondary level, it increased from 152 to 168.

Officials say this reflects expanding opportunities in the education sector and the perception of teaching as a profession that offers stability, social acceptance and some degree of flexibility. The shift is evident not only in staffrooms but also in classrooms. The data shows that female enrolment in higher education crossed 50% in 2023 to 24, rising from 49.08% the previous year.The 2021 to 22 figures included in the same report highlight women’s growing presence in advanced programmes as well. The number of female students for every 100 male students increased in MPhil, postgraduate, undergraduate and diploma courses. The direction of movement is clear. Women are choosing to study and specialise in greater numbers.

The labour market presents a very different picture

Despite these gains, the worker population ratio for women in Delhi was only 14.2% in 2023 to 24. For men, it was 52.8%. The contrast becomes sharper when compared with national figures reported in the same dataset, where women recorded a worker population ratio of 30.7%.A similar gulf appears in the labour force participation rate. In Delhi, women recorded 14.5% in 2023 to 24. The national average for women was 31.7%. Men in Delhi recorded 54%, close to the all India level.Officials say the gains in education have not translated into paid work because of deeper structural constraints. They point to cultural expectations, concerns around safety in travel and a lack of job options that align with women’s needs. These factors limit not only participation but also the kind of work women feel they can pursue.

What work women do and what they avoid

The report notes that 70.2% of working women in Delhi are regular wage or salaried employees. Only 26.4% are self-employed and 3.4% are in casual labour. Men show a very different distribution, with a higher share in self employment and informal work. This imbalance indicates that women rely more on stable jobs and have limited access to entrepreneurial or flexible opportunities. It also signals lower economic autonomy.Rural Delhi reflects an even more restrictive environment. The worker population ratio for women dropped to 2.9% in 2022 to 23 before rising to 11.1% in 2023 to 24. The volatility shows how quickly women fall out of the labour market when conditions change.Delhi’s unemployment rate, reported as part of the same dataset, was lower than the national average for both genders in 2023 to 24, at 2.2% for men and 1.5% for women. However, this low figure does not signal opportunity. It often indicates withdrawal. Women who are not counted as unemployed may not be seeking work at all.

A gap that education alone cannot close

Delhi’s data shows that gains in education do not ensure gains in employment. Women are present in classrooms as teachers and students but remain largely absent from the city’s economic activity. The labour market has not adapted to the realities of women’s lives, and the availability of education has not been matched by the availability of work that women can safely and sustainably access.The report, published by the Directorate of Economics and Statistics, offers a clear pattern that policymakers will need to confront. Learning has risen. Earning has not. The gap sits not in aspiration or ability but in the structure of the labour market that surrounds women in the city.