Imagine hearing a sound that began its journey before our galaxy even existed. That is what astronomers are doing now. They are picking up faint signals that have travelled for more than 13 billion years to reach Earth. These signals come from a time when the universe was still very young, long before the Milky Way took shape.This is like reading the universe’s earliest diary pages. Not through digging or fossils, but by studying very weak radio and microwave signals left behind after the Big Bang.The Milky Way came together billions of years after the Big Bang. But some light and radio waves we detect today were emitted during the universe’s first billion years. These signals have been travelling ever since, slowly stretched by the expansion of space, until they finally reached our telescopes.In a rare achievement, astrophysicists from the CLASS (Cosmology Large Angular Scale Surveyor) project have detected a 13-billion-year-old microwave signal from the Cosmic Dawn using Earth-based telescopes in the Andes mountains of Chile.Funded by the US National Science Foundation, this team, led by professor Tobias Marriage of Johns Hopkins University, captured faint polarised microwaves that reveal how the first cosmic structures influenced light left over from the Big Bang. This marks the first time such a signal has been detected from the ground, defying earlier assumptions that only space telescopes could achieve this.

.

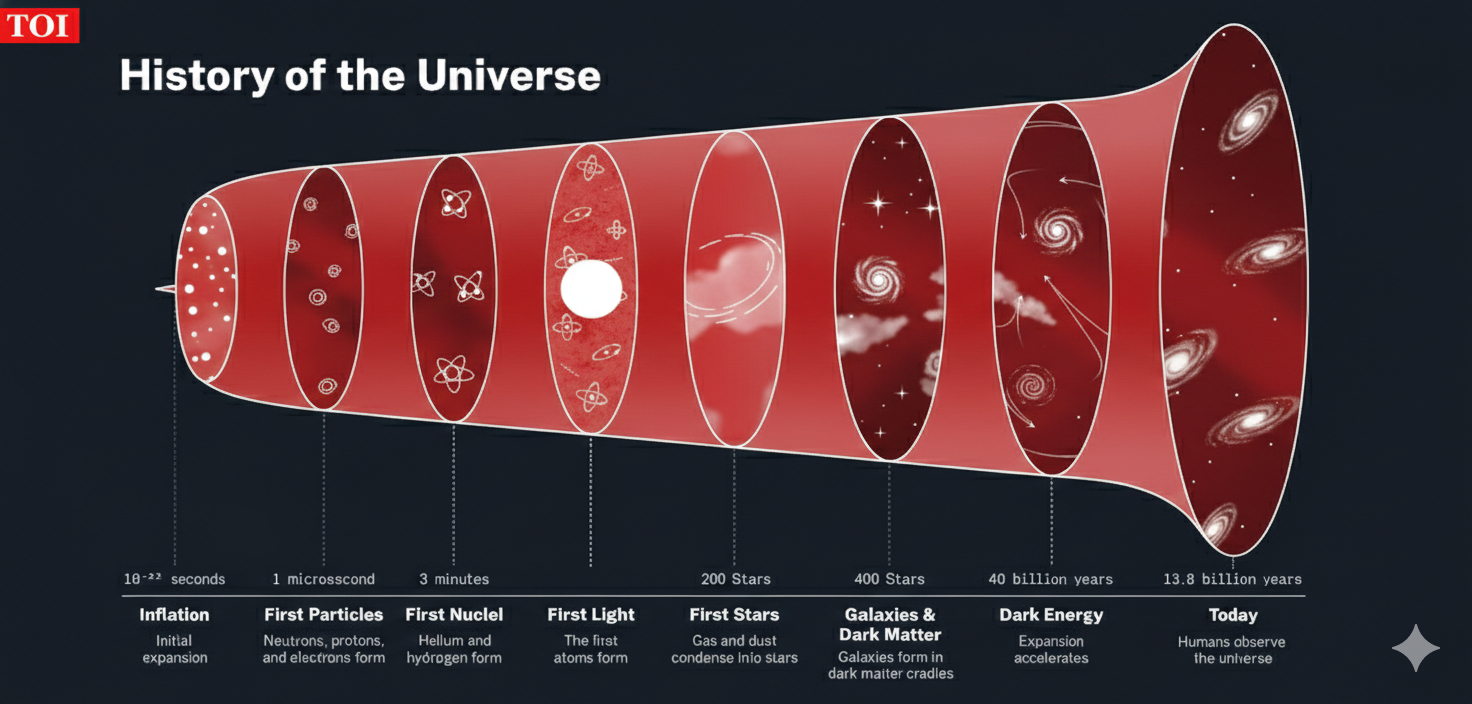

Universe’s early timeline

Right after the Big Bang, the universe was hot and dense. As it cooled, particles joined together to form neutral atoms. About 380,000 years later, light could finally move freely. This light still exists today as the cosmic microwave background.After that came a long dark period. There were no stars, no galaxies, and no visible light. This phase is called the Cosmic Dark Ages.Between about 50 million and one billion years after the Big Bang, the first stars and galaxies began to form. Scientists call this period the Cosmic Dawn. Signals from this time are especially valuable because they show how the universe moved from darkness to light.Known as Population III stars, the early stars were massive, composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, and burned out quickly. Their ultraviolet radiation ionised surrounding hydrogen gas, allowing light to travel freely and marking the universe’s transition from darkness to light.“It’s one of the most unexplored periods in our universe,” a research scientist at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Perth, Australia, told Live Science. “There’s just so much to learn.”

The signal scientists are chasing

One of the most important clues from the early universe comes from hydrogen. Hydrogen filled most of space after the Big Bang. Neutral hydrogen naturally produces a weak radio signal known as the 21-centimetre line. By tracking this signal, scientists can learn how hydrogen behaved billions of years ago and how the first stars and black holes affected it.As the universe expanded, this signal was stretched to longer wavelengths. Its polarisation, meaning the waves align in specific directions, can reveal the distribution and motion of early matter, providing a map of the universe’s large-scale structure. This makes polarisation a key tool for understanding cosmic evolution.Unlike light from distant galaxies, which can be very hard to see, the hydrogen signal tells a bigger story. It shows what was happening across huge regions of space, not just where bright objects existed.These ancient microwaves are not only faint but also polarised—meaning their waves align in specific directions due to interactions with early matter. Detecting them from Earth is extremely challenging because they are easily drowned out by terrestrial radio noise, satellites, and atmospheric conditions.The CLASS team overcame these challenges by using high-altitude sites in Chile, cross-referencing their data with space missions like Nasa’s WMAP and ESA’s Planck, and carefully filtering interference to isolate the genuine cosmic signal.Projects like REACH and the future Square Kilometre Array (SKA) are designed to expand these observations and detect similar signals across the universe.When the first stars switched on, they gave off ultraviolet and X-ray radiation. This changed how hydrogen behaved. Those changes are recorded in the 21-centimetre signal. By studying its strength and pattern, scientists can work out when the first stars formed and how powerful they were.

How astronomers detect old signals

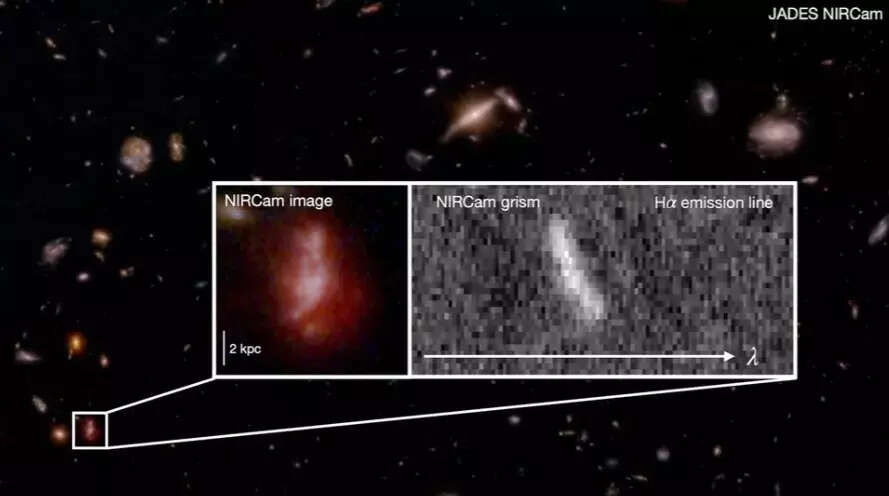

Telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope look for light from early galaxies. But for these ancient hydrogen signals, scientists rely on radio telescopes.Radio observations complement optical and infrared studies. While JWST shows the actual galaxies and stars forming, radio signals reveal the state of the surrounding gas and large-scale structures. Together, they give a fuller picture of the early universe.These ancient signals are extremely weak, easily buried under radio noise from Earth, satellites, and our own galaxy. That is why scientists need very sensitive instruments and remote locations. Future observatories may even be placed on the Moon, where Earth’s interference is blocked.

.

Picture: James Webb telescopeJWST has already found surprisingly mature and chaotic galaxies from the universe’s early years. Combining JWST data with radio measurements allows scientists to understand both the environments and the galaxies themselves.

What a13-billion-year-old signal reveals

Recent observations from ground-based telescopes in Chile have picked up signals dating back around 13 billion years. These signals suggest that hydrogen gas was already being affected by energetic radiation during the Cosmic Dawn.This shows that stars influenced their surroundings much earlier than previously thought. By examining polarisation and 21-cm signal patterns, researchers can estimate star formation rates, star sizes, and the intensity of early starlight.The earliest stars were not like the ones we see today. They formed from hydrogen and helium, with almost no heavier elements. Scientists believe these stars were very large and burned out quickly.Observations also indicate that early galaxies formed faster and were more chaotic than expected. This challenges older ideas about gradual structure formation and raises questions about how matter clumped together so quickly.

What comes next in search for Cosmic origins

Despite new discoveries, many things remain unclear. Scientists still want to know exactly when the first stars formed, how massive they were, and how quickly galaxies grew.They also aim to understand how early black holes shaped their surroundings and the intergalactic medium. Future instruments like SKA, REACH, and Moon-based observatories may finally resolve these mysteries.Learning about the universe’s first billion years helps scientists understand how everything came to be. It informs theories about matter, energy, and the forces that shape the cosmos.Even though we cannot travel back in time, these ancient signals allow us to read the universe’s earliest chapters.By examining polarised microwaves, scientists trace how early stars and galaxies influenced their surroundings, shaped large-scale cosmic structures, and laid the foundations for modern galaxies. Ground-based technology is now enabling discoveries that once only space telescopes could achieve.Detecting signals older than the Milky Way is altering our understanding of cosmic history. By combining radio observations with powerful optical telescopes, scientists are slowly building a clearer picture of the universe’s earliest days.Each new signal adds another piece to the story of how darkness gave way to light, and how the universe we live in today first began to take shape. The next decades promises even more revelations about the Cosmic Dawn, its stars, galaxies, and the origins of the cosmos itself.