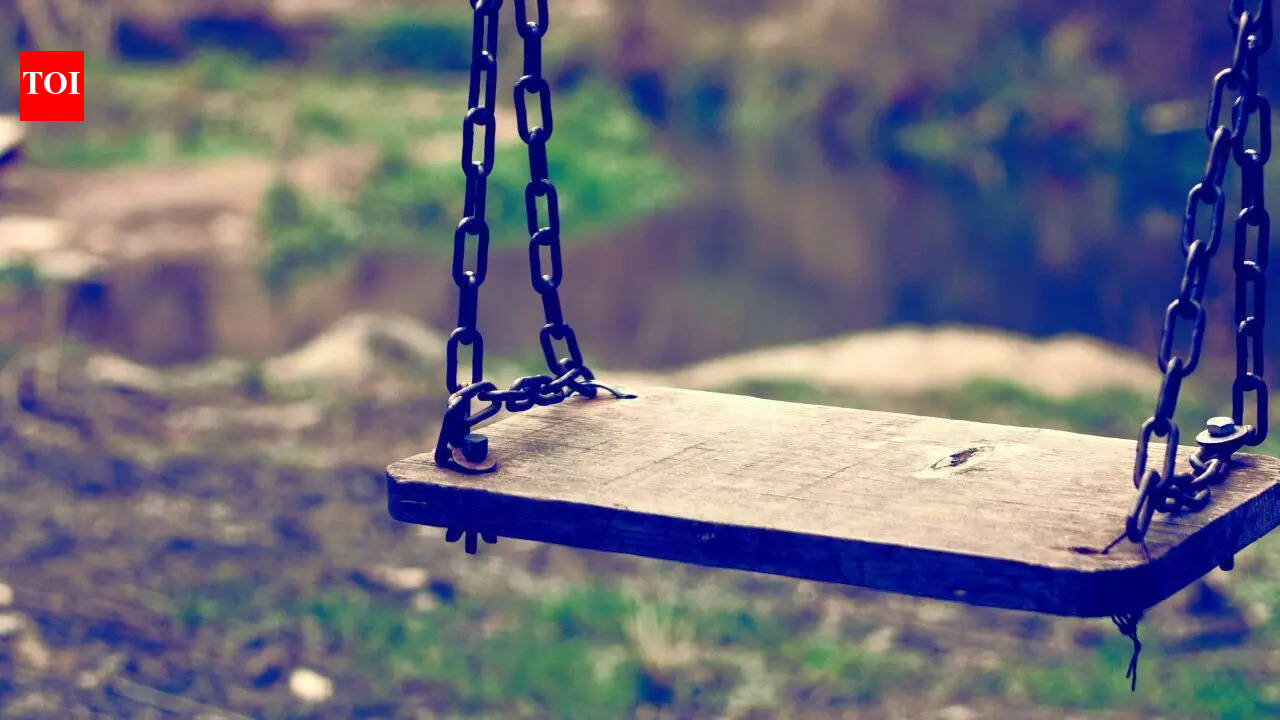

When five-year-old Inika Sharma visited Sunder Nursery this weekend, she had no idea that a simple outing would turn into an experience her parents had spent years trying to shield her from.All Inika wanted to do was sit on a swing. She was refused. When her parents asked why, the security guard allegedly said, “Bachche ka dimaag sahi nahi hai” (the child is not mentally sound).What followed was a painful confrontation. Inika’s mother, Mona Mishra, visibly shaken and deeply upset, questioned why her child could not be allowed on a swing when she was accompanied by her parents and under their supervision. This small, reasonable request led to a verbal altercation, with the guards unwilling to listen or understand. Other parents eventually stepped in to support Inika’s family.

“Till now, Inika thought she could do anything. But for the first time, her confidence was shaken,” her father Raman Sharma recalls. “She became visibly upset and said, ‘Papa, chalo, ye nahi karna mujhe’ (Papa, let’s go, I don’t want to do this). My heart broke. This is exactly what we had been trying to prevent—that she should never believe there is anything in this world she cannot do.”So who is Inika?A child with disabilities?No.Inika is a miracle.Inika’s mother, Mona Mishra, had a normal pregnancy. On the day of delivery, doctors assured her that everything was fine and that Inika would be born by 9:30 am. But at 8:45 am, something went terribly wrong. The baby got stuck, panic ensued, and an emergency C-section was performed. Inika was born almost lifeless.She was immediately shifted to the ICU. When she didn’t cry for ten days, doctors told the family she might not survive. When the parents asked how much hope there was, the answer was blunt: zero percent. Against medical advice—and after signing an affidavit—the parents took their child home.Inika was diagnosed with the severest form of brain injury, HIE Stage 3. The MRI showed extensive brain damage. Doctors told her parents that if she survived, she would likely remain bedridden for life-unable to walk, talk, or eat without medical support.

But her parents refused to accept that fate.Therapy began when Inika was just 17 days old. “The first few months were the hardest,” her parents say. “She couldn’t swallow, suck, hold her neck up, or respond to anything. We gave up our personal lives completely—no social events, no outings, no breaks. We lived every second for her. Even bathing once in two or three days felt like a luxury. But slowly, things changed.”Inika began responding. She smiled. She reacted to sounds. She learned to sit, then to stand independently. Hope returned.Yet walking remained elusive. Years of therapy passed, but Inika could not take her first steps. Her balance was severely affected due to injury to the cerebellum. At one point, doctors advised a wheelchair, saying she might never learn to walk.Giving up, however, was never an option.Her parents tried everything—traditional therapy, NDT, hippotherapy, hydrotherapy, and even treatments abroad, followed by intensive home sessions. And then, one day, Inika took a few wobbly steps.It was a miracle-for her family and for her doctors.Inika’s father, Raman Sharma, credits his employer, Larsen & Toubro, for allowing flexible work hours so he could be present for his daughter. He is equally grateful to Mirambika School, which not only accepted Inika but also played a crucial role in her overall development. “We need more schools like this,” he says. But the larger question remains:Is the world ready to accept Inika?If a child is denied a swing in a public park, what can we expect from society at large? Different children are not inferior. Yet how many public spaces truly reflect inclusivity? How many highways have accessible toilets? How many parks have ramps for wheelchairs? How often do we see genuine effort to accommodate children who may not move, think, or learn like others?Inclusivity is often discussed—but is it truly practiced?Raman Sharma and Mona Mishra are examples of what unwavering determination and positivity can achieve. They brought life and dignity to a child even doctors had given up on. Is it too much to ask society to meet them halfway—with empathy, understanding, and basic humanity?As a collective, we must ask ourselves:Are we truly ready to accept children like Inika?Because acceptance should not be harder than hope.