On a cold Tehran night, an elderly woman walked through a crowd of protesters, chanting against the state. Her mouth appeared bloodied. She did not slow down. “I’m not afraid,” she shouted. “I’ve been dead for 47 years.”The video, filmed during Iran’s most recent wave of anti-government demonstrations, spread rapidly online. Whether the red streaks on her lips were blood or paint almost felt beside the point. For millions of Iranians—especially women—her words captured a truth lived quietly for decades: a sense that life, in its fullest sense, was taken long ago.Today, as Iran grapples with a collapsing economy, rising inflation, and international isolation, women are once again standing at the door of dissent. Economic despair has reignited mass protests, but the streets are echoing with something older and deeper than anger over prices. Women are using this moment to reclaim a struggle that has defined generations—a fight for bodily autonomy, dignity, and the right to exist without fear.The slogan chanted across cities and villages alike is familiar now, inside Iran and far beyond it: “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” — Woman, Life, Freedom.

Jin , Jiyan, Azadi: A slogan born of blood

“Woman, Life, Freedom” did not begin as a chant. It emerged from Kurdish feminist movements long before it became a global rallying cry. In Iran, its meaning crystallised on September 16, 2022, with the death of Jina Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman detained by the morality police for allowing strands of hair to escape her hijab.

Mahsa Amini has become the face of Kurdish movement for women.

Witnesses said she was beaten. Authorities denied wrongdoing. The United Nations later found Iran responsible for the “physical violence” that led to Amini’s death. Amini died in custody, and the denial only deepened public fury.Her death triggered the largest protests Iran had seen in years. Women burned headscarves, cut their hair in public, and faced armed security forces with bare faces and raised voices. More than 500 people were killed during the crackdown. Over 22,000 were detained.

When morality becomes mandatory

To understand why Iranian women continue to risk everything, one must return to 1979.In the late 1970s, Iran was already in turmoil. Street battles erupted between demonstrators and forces loyal to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Cinemas burned. Officials were attacked. Each funeral for a slain protester became the spark for another demonstration. By early 1979, millions were on the streets.Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile, promising justice and independence. Many Iranians—women included—did not fully grasp what his vision of ‘Velayat-e Faqih’, or ‘Guardianship of the Jurist’, would mean in practice.The consequences came swiftly. Thousands of former officials, writers, activists, and military officers were executed. A brutal eight-year war with Iraq followed. And then came a quieter, more enduring transformation: the imposition of mandatory hijab and the systematic rewriting of women’s lives through law.What began as ideological control hardened into a legal framework designed to discipline women’s bodies, choices, and futures.

Mandatory hijab – how it started

Law as a tool of submission

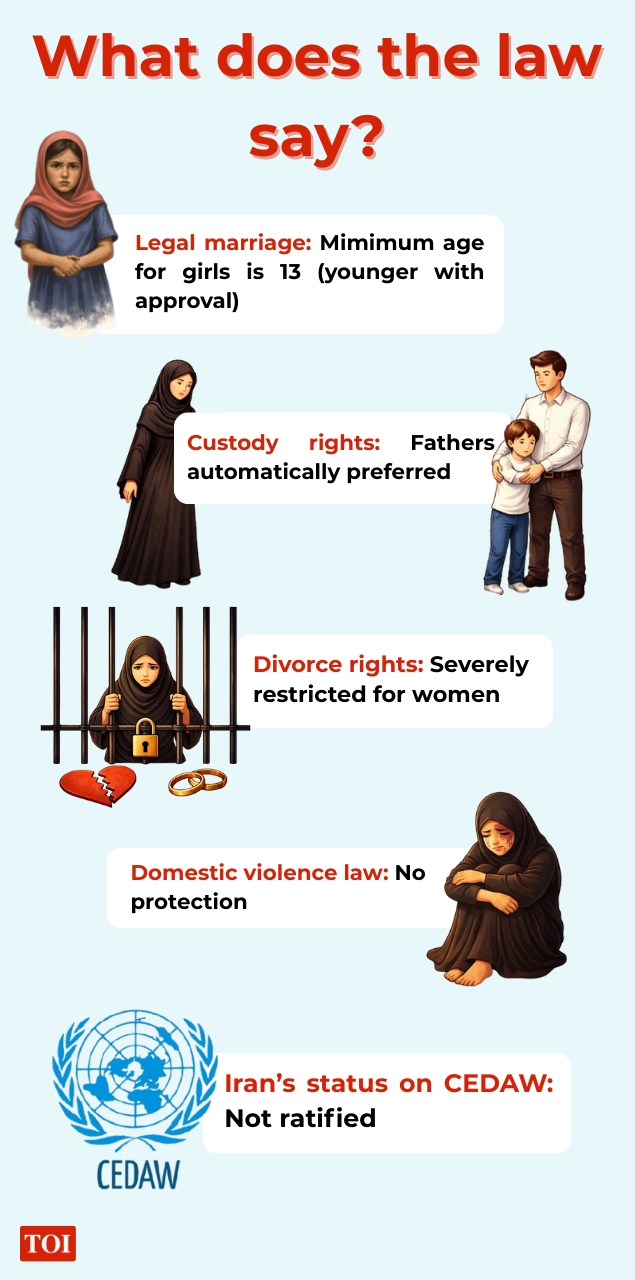

Today, Iranian law allows girls to be married at 13, younger with approval of male guardian and judicial. Women face enormous barriers to divorce and often lose custody of their children if they leave abusive marriages. Domestic violence is widespread, yet routinely dismissed by police as a “family matter.”Iran has not ratified the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Protective mechanisms for abuse victims are almost nonexistent. Leaving home often means forfeiting financial support and children alike—a reality that traps women in violent households and, in many cases, leads to fatal outcomes.The control extends beyond the home. In recent years, the government has restricted which university majors women may pursue, limiting access to fields like engineering, education, and counselling. Professors who resist face harassment or dismissal. Students who protest are detained.Yet universities remain among the most defiant spaces in Iran. Every major protest movement—from the 1999 student uprising to the present—has been powered by young people, many of them women. As one Iranian expression puts it, they keep alive koorsoo — a small, stubborn flame of hope.

The everyday struggles of Iranian women.

Symbols of defiance

In moments of repression, symbolism becomes language.In one viral video, a woman believed to be an Iranian refugee in Canada set fire to a photograph of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. She lit a cigarette from the burning image and let the ashes fall to the ground.In 34 seconds, she breaks multiple taboos: – appearing without a hijab– destroying the image of the country’s highest authority — a crime punishable by death– smoking, an act deemed immodest for women. Whether staged or spontaneous, the gesture resonated globally. Soon, similar acts appeared from Israel to Germany, Switzerland to the United States.Inside Iran, defiance is more dangerous.In Mashhad, a woman had climbed naked onto a police vehicle after allegedly being assaulted for improper hijab. Armed officers hesitated as she shouted and raised her arms, using her own body as a weapon against shame.At Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport, another woman confronted a cleric who challenged her attire. She removed his turban and placed it on her own head. “So you have honour now?” she asked, the question cutting through centuries of imposed morality.

The cost of resistance

Resistance in Iran carries a steep price, and women are paying it with their lives.Human rights groups have documented the killing of female protesters during recent crackdowns. Among them was Sholeh Sotoudeh, a pregnant mother of two, shot dead in Gilan Province. Another, Ziba Dastjerdi, was reportedly killed in front of her daughter.Executions continue as a tool of terror. Zahra Tabari, a 67-year-old engineer and activist, was sentenced to death following what supporters describe as a sham 10-minute remote trial. Her alleged crime: holding a banner that read “Woman, Resistance, Freedom.”According to Iran Human Rights, over 40 women have been executed in 2025 alone.Even art is punished. Pop singer Mehdi Yarrahi was flogged 74 times for releasing a song ‘Soroode Zan’ urging women to remove their headscarves. “The person who is not willing to pay a price for freedom is not worthy of freedom,” he wrote afterward. His words echoed across campuses, where his music remains an underground anthem.

A global echo

The world has not been silent.More than 400 prominent women worldwide—including Nobel laureates and former heads of state—have demanded the release of Zahra Tabari. UN experts warn her case reflects a broader pattern of gross violations and the misuse of capital punishment.Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai highlighted the decimating freedom of Iranian women, stressing that restrictions extend far beyond education into every aspect of public life. Iranian activists in exile, journalists, and artists continue to amplify voices from inside the country, despite threats to families back home.

When women lead

Every protest wave in Iran eventually returns to women, because women experience the state most intimately—on their hair, their clothing, their marriages, their classrooms.Economic collapse may bring crowds to the streets, but it is women who articulate what is fundamentally at stake. Their protest is not only against poverty or corruption; it is against a system that demands submission as the price of survival.History suggests that regimes which wage war on women and intellectual institutions lose more than control—they lose legitimacy. Iran’s universities, homes, and streets are becoming spaces where fear no longer fully works.The elderly woman in the night march understood this. She had survived decades of repression. Her body bore the cost. Yet she walked on.“I’ve been dead for 47 years,” she said—not as surrender, but as indictment.For Iranian women, protest is not a moment. It is a condition of life.And as long as they keep chanting ‘Jin, Jiyan, Azadi!’ the struggle—quiet or loud, symbolic or bloody—will not end.