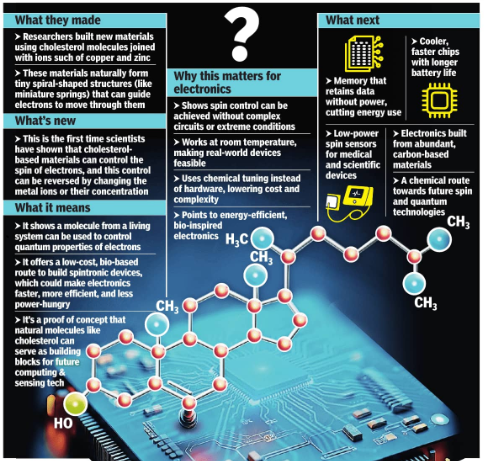

Cholesterol, best known for its link to heart disease, may play an unexpected role in future electronics. Indian researchers have found that this waxy molecule, which doctors routinely measure in blood tests, can control one of the fundamental properties of electrons — their spin.Today’s computers ignore this property entirely, using only the electron’s charge to store and process information. Now, a generation of devices called spintronics (short for spin electronics) aims to exploit both the charge and the spin of the electron. And that’s where cholesterol can help.

Why it matters

If today’s computers are like offices needing constant power supply to keep files from disappearing, spintronic devices can be like paper files that stay functional even when the power is off. Your laptop might boot instantly instead of taking minutes to start, and your phone could retain apps exactly where you left them even after the battery drains.Beyond convenience, such devices could also cut heat and power use. Less heat means longer-lasting gadgets and fewer noisy cooling fans. For data centres that power everything from streaming services to AI, even the smallest gain in energy efficiency could lead to huge savings in electricity costs and carbon emissions.The change could also ripple into areas we rarely associate with physics labs. Spin-based memory could make medical devices, smart watches, and electric vehicles more efficient. A heart monitor that records signals continuously without draining its battery, or an EV that uses smaller, cooler chips to manage energy flow, could both benefit from this kind of lowpower operation.

–

In a broader sense, this research hints at a convergence of biology and electronics, where materials inspired by living systems lend new capabilities to machines. Just as solar cells borrowed ideas from photosynthesis, spintronics borrows from molecular chirality to build systems that think and adapt more naturally. Like a left-handed glove that won’t fit a right hand, cholesterol molecules have a specific ‘handedness’ called chirality.

Nature’s blueprint

Imagine a spiral staircase that winds only one way. Someone carrying a long stick will find it easier to climb if they hold it in one direction; turn it the other way, and the staircase becomes difficult to navigate. Chiral molecules act in a similar way: they allow electrons with one spin orientation to pass through more easily while blocking those with the opposite spin.The team at the Institute of Nano Science and Technology (INST), Mohali — Amit Kumar Mondal, Rabia Garg, Pravesh Singh Bisht, Nidhi Bhatt and Nagaraju Nakka — has found a way to control which direction that staircase winds. They added different metal ions — charged atoms such as zinc and copper — to cholesterol-based structures. With zinc, electrons spinning one way zipped through; with copper the preference flipped. It’s a bit like replacing the handrail of a spiral staircase and finding that everyone must now climb it the other way round.

Tuning the spin

The researchers built large molecular structures, where cholesterol molecules stack together in helical arrangements, held in place by metal ions. These helices form naturally, like DNA’s double helix, but unlike DNA, their twist direction can be reversed by tweaking metal content.By changing the type or concentration of the metal, they could finetune the spin preference. At low copper levels, the helices twisted one way; as more copper was added, the twist reversed, and with it, the flow of preferred spins.They recorded spin polarisation values as high as 87% — nearly nine out of 10 electrons emerging from the material had the chosen spin. The measurements were made using delicate instruments that track current flow under magnetic fields, like a record player’s needle tracing grooves, but at the nanoscale.

From lab to life

For now, the experiments exist only in thin films a few nanometres thick, studied under lab conditions. But if scientists can scale this up, the implications are wide. Electronics based on biological molecules could be flexible, biodegradable, and even self-healing (imagine wearable sensors that mould comfortably to skin or devices that degrade harmlessly after use).This idea of borrowing nature’s solutions for technology is not new, but cholesterol’s foray into spintronics is a pleasant irony: The molecule that is linked to health problems may one day make our electronics leaner, faster, and more sustainable.