“Now, what I want is, Facts.” The demand, delivered by Thomas Gradgrind in Charles Dickens’ Hard Times, is not a plea for truth but a warning about method. In Dickens’ Coketown, facts are not meant to illuminate human life, they are meant to discipline it. Workers are reduced to figures, usefulness is measurable, security is incidental. Employment exists, but certainty does not. One is always working but never settled.A century and a half later, the vocabulary has changed, but the condition has not. The modern workplace has found a way to preserve productivity while hollowing out assurance. Glassdoor’s Worklife Trends 2026 gives this condition a name. It calls it the ‘forever layoff’, defining it as a pattern where layoffs are “ongoing, with job cuts coming in never-ending waves instead of a tsunami.” The data is as precise as Gradgrind would have liked it: Layoffs affecting fewer than 50 employees now make up 51 per cent of all layoffs in 2025, up from 38 per cent in 2015. The event has been broken down into increments, the ending postponed indefinitely.What replaces the spectacle of mass dismissal is something subtler, and arguably more corrosive. The psychology of the forever layoff is not panic but permanence. Shock passes. Uncertainty lingers. Workers are neither dismissed nor secure; they remain inside the system, alert to silence, responsive to signals, performing continuity under conditions that offer none. Psychologists call this state chronic uncertainty—a stressor known to heighten vigilance while steadily eroding trust.Dickens understood this long before management science did. In Hard Times, the cruelty is not starvation but conditionality. To be useful is not to be safe; to be employed is not to belong. The forever layoff inherits that logic perfectly. It does not end careers. It suspends them. It is not an economic accident but a design choice—one that turns facts into instruments and makes the absence of an ending the most efficient form of control.

Permanent trial mode: The anatomy of forever layoffs

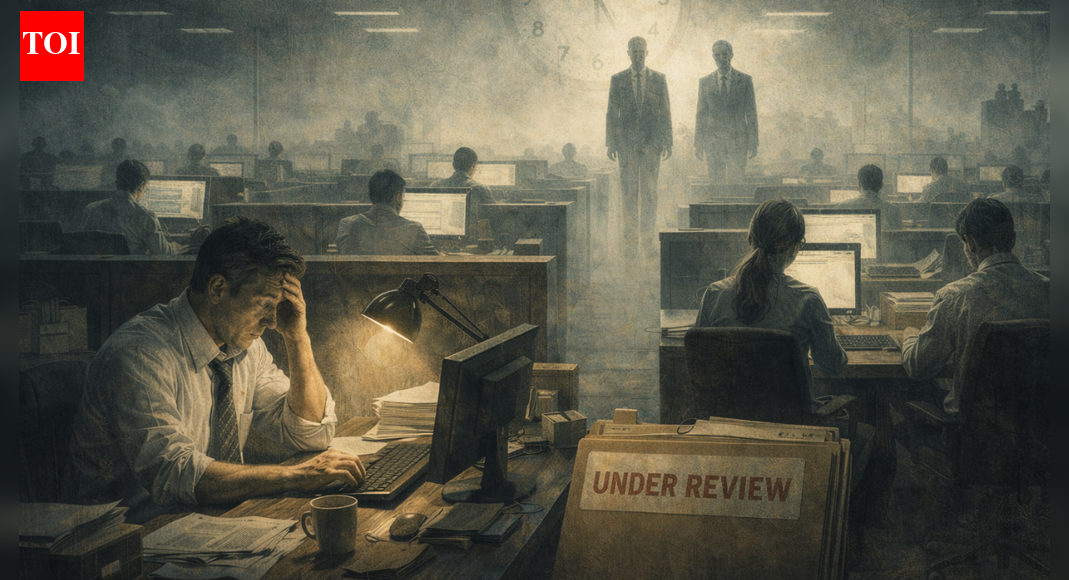

What Glassdoor identifies as the forever layoff marks a quiet but decisive shift in how institutions now reduce staff. Instead of singular moments of rupture—one announcement, one list, one reckoning—layoffs arrive in increments. Small numbers at a time. Sometimes fewer than fifty. Often framed as restructuring, role realignment, or cost correction. The organisation stays standing, the work continues. What disappears is not employment itself, but the assurance attached to it. Whoever remains keeps watching. This pattern produces a workforce that is neither secure nor dismissed, but permanently under review—alert to signs, decoding silences, treating continuity not as safety but as postponement.It is here that Franz Kafka becomes uncannily contemporary. In his novel The Trial, the protagonist, Josef K., is arrested one morning in his lodging house. The scene is deliberately untheatrical. Two unnamed officials appear. They are calm, almost courteous. K. is informed that he is under arrest, yet nothing that normally follows an arrest occurs. He is not taken into custody. He is not confined. He is told only that a trial is pending. Breakfast is eaten. The day proceeds. K. goes to work.The visual logic is crucial. Authority does not drag K. out, it settles into the room. The arrest looks mild because it is procedural, not violent. And precisely because it is incomplete, it takes over his inner life. From that moment on, K. lives inside an unresolved process. Every interaction acquires weight. Every delay feels meaningful. His freedom remains intact; his certainty does not.This is the same condition produced by the forever layoff. Employees are not expelled from institutions; they are left inside them, performing, complying, waiting. Like Josef K., they are not told what the charge is, or when the matter will be resolved. A mass layoff ends the story for those affected. The forever layoff suspends it for those who remain.Kafka understood something management science has only recently rediscovered: Uncertainty is more efficient than force. A trial without a verdict disciplines more effectively than a sentence ever could. In workplaces shaped by serial, small-scale layoffs, the arrest has already happened. The trial is pending. And work, outwardly unchanged, quietly reorganises itself around that fact.

The slow poison of the forever layoff: What it does to work and the people who do it

Forever layoff is not a firing squad. It is a drizzle. It rarely arrives as a single day of reckoning; it arrives in instalments—small cuts, periodic “realignments,” quiet departures that do not disrupt the building’s lights or the calendar’s rhythm. The institution remains upright, and that is precisely why the experience becomes psychologically peculiar. Nothing ends. Nothing resets. People are not told that security has been withdrawn; they discover it by watching who disappears next.A shift in mindspaceThe first casualty is time. In a stable workplace, time has length; careers are imagined in arcs. Under serial, small-scale cuts, the future contracts. Employees stop planning in years and start planning in weeks. Ambition becomes tactical. Learning becomes selective. Long bets begin to look like naïveté.A second shift follows. Attention becomes interpretive. Silence stops being neutral. A delayed reply, an unexplained meeting, a sudden change in tone—small signals acquire weight. People start reading the workplace like a text that might contain a hidden warning. They keep working, but part of the mind is always scanning.Productivity becomes performativeProductivity does not fall immediately; it often rises. After all, fear is an accelerant. But it is an impure fuel. It pushes people towards work that can be proved rather than work that must be trusted. Dashboards thrive. Visibility becomes a survival strategy.Deep work suffers quietly. So does invention. Employees hesitate to take risks that might fail publicly in an environment where failure can be misread as expendability. Organisations may demand innovation in speeches, but they reward legibility in practice. This is how workplaces end up with motion without progress—activity without long-term creation.Trust thins, rumours thickenWhen layoffs arrive in small batches and explanations remain partial, culture begins to fill the gaps with interpretation. Who left, and why? Who is safe, and on what terms? Trust erodes not because management is always dishonest, but because the narrative is always incomplete.Colleagues become cautious with one another. Conversations turn careful. Mentorship weakens, not out of selfishness but out of self-protection. Rumour spreads because uncertainty demands stories, and the workplace provides too few facts with which to write them.Power moves to the keepers of informationIn the forever layoff, authority shifts from hierarchy to proximity. Those closest to decisions—those who know what is coming, even vaguely—acquire quiet power. Ambiguity becomes leverage.Employees adapt by managing perception. They learn to be visible but not controversial, useful but not expensive, present but not exposed. Managing up becomes less a career tactic than a form of insurance. Work becomes political not because people become worse, but because uncertainty makes everyone strategic.The workplace turns into a waiting roomThe final impact is existential. The institution continues to function, but it stops offering belonging. People remain employed, yet feel provisionally placed. The office becomes a waiting room with no clock and no announcement. The verdict is always pending.

Careers at the edge of certainty

In Hard Times, Dickens warned that a civilisation trained to worship facts would eventually forget people, reducing labour to arithmetic and dignity to output. In The Trial, Kafka went further, showing how power no longer needs punishment when it can survive on postponement. Today’s workplace has fused the two. Careers are measured relentlessly and judged endlessly, yet rarely concluded.For workers, this marks a brutal recalibration. The promise is no longer stability, but survivability; not belonging, but relevance. To stay employable is to stay alert, adaptable, and quietly replaceable. That may keep the institution efficient, but it leaves the individual unmoored.The risk is not that work becomes harder. It is that insecurity becomes normalised, even internalised, as the price of ambition. A career built entirely inside permanent trial mode may endure—but it will do so thinner, shorter, and far more cautious than it once was.