Archaeologists have spent decades debating how and when people first entered the Americas. The outlines are familiar, but the details keep shifting. A growing body of evidence now suggests that the earliest populations arrived earlier than once believed and brought with them a shared way of making stone tools. This emerging picture is based not on a single site or dramatic find, but on patterns seen across tool assemblages dated to before about 13,500 years ago. Researchers argue these tools belong to a broader technological tradition with roots in Northeast Asia. The idea does not settle old arguments, but it does change where many are now looking. Instead of focusing only on land bridges, attention is drifting towards coastlines, islands, and older connections that are harder to trace.

New evidence ties the first American’s stone tools to ancient Japan

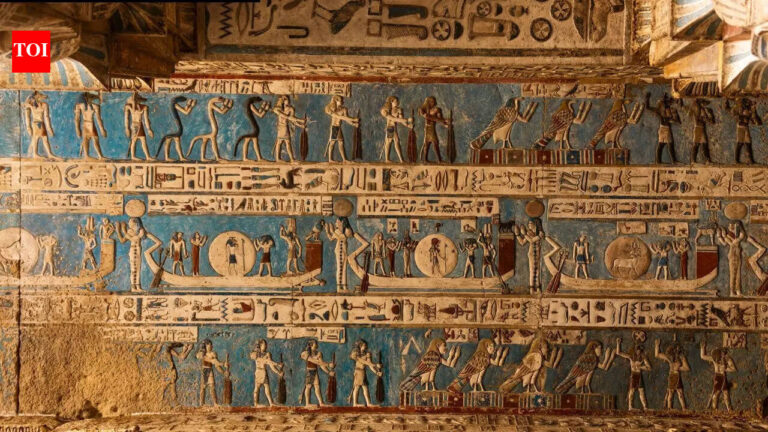

Across North America, several early sites show similar approaches to making tools. These assemblages often combine two methods. One uses cores shaped to strike long blades. The other relies on carefully flaked bifaces shaped from both sides. These methods were sometimes used together, producing small projectile points with refined forms.While the finished tools vary from place to place, the underlying process looks familiar. Blades were used as cutting tools or reshaped into scrapers and points. Bifacial tools produced flakes that were also put to use. This shared logic suggests knowledge passed along, rather than isolated experiments.

Researchers are revisiting the idea of an American Upper Palaeolithic for several reasons

The study “Characterising the American Upper Palaeolithic” refers to these assemblages as part of an American Upper Palaeolithic. The term has been controversial, especially when applied outside Europe. Still, supporters argue it helps place early American tools within a wider global context. The same dual-blade and biface techniques appear across much of Eurasia during the Late Upper Palaeolithic. Seeing similar choices in early American sites suggests a connection that is technological rather than symbolic. It points to learnt practices carried by people moving across regions, adapting but not starting from scratch.

How northeast Asia fits into the picture

Comparable stone tool traditions appear in Northeast Asia, including northern Japan, around 20,000 years ago. Sites there show elongated blade production alongside bifacial points with similar cross sections and shaping strategies.Researchers note that some of these Asian points share specific design features with early American examples. This does not mean they are identical, but the resemblance is close enough to raise questions about shared origins. It suggests that the ancestors of the first Americans were part of a broader population already using these methods.

The first Americans could have come by the coast

Genetic studies suggest that the founding population of the Americas formed in northeast Asia around 25,000 years ago. After a long period of isolation, this group expanded into the Americas sometime after 20,000 years ago. Where that isolation happened remains unclear. One proposal places it in the Paleo Sakhalin-Hokkaido-Kuril region. During the last glacial maximum, lower sea levels connected these areas into a long peninsula. People living there would have had access to rich coastal resources and island chains. From this setting, a gradual movement along the Pacific coast becomes plausible, even likely.

Why inland routes leave unanswered questions

The traditional land bridge route through Beringia has gaps that are hard to ignore. Few archaeological sites from the last glacial maximum have been found there. Glacial conditions would have made long stays difficult. In contrast, coastal routes leave fewer traces, especially with rising sea levels since the ice age. Campsites and travel corridors may now be underwater. This absence of evidence does not confirm the coastal model, but it does make it harder to dismiss.

What the early dates across North America suggest

Some pre-Clovis sites across North America date to between 18,000 and 13,500 years ago, with claims of even earlier presence. The widespread nature of these sites implies time for movement and adaptation. If people were already dispersed across large areas by 16,000 years ago, their arrival must have begun earlier. Stone tools alone cannot give a full answer, but they provide one of the few durable records left behind.

Why the story remains open

Despite growing support, many questions remain. Not all sites are accepted. Tool styles vary. Genetic data still lacks geographic precision. The proposed homeland in northern Japan or nearby regions is plausible but not proven. What is changing is the tone of the discussion. The old certainty has softened. In its place is a quieter recognition that the first Americans may have come by less obvious paths, carrying traditions shaped long before they reached a new continent.