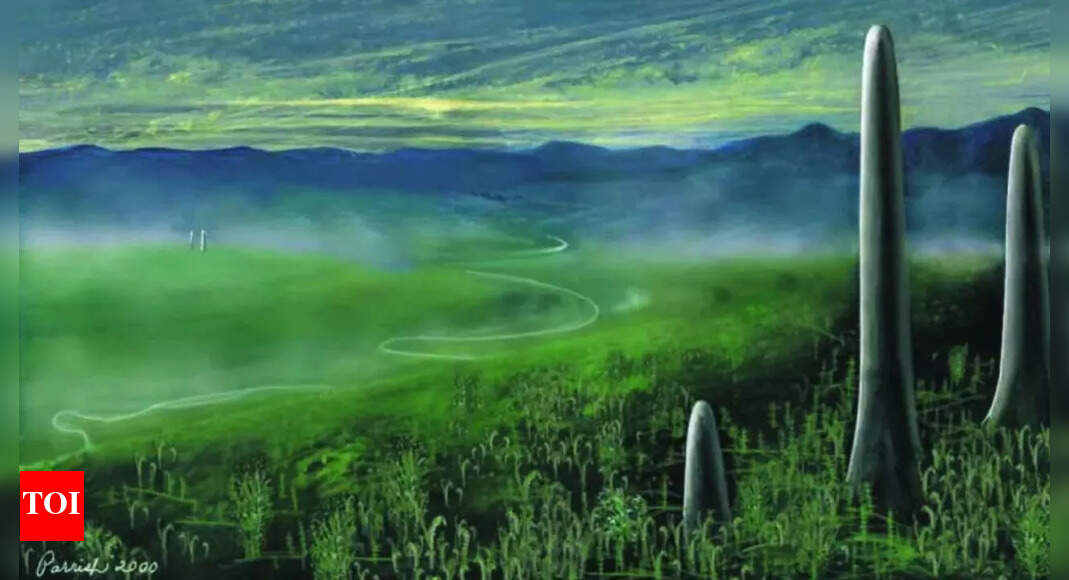

For centuries, plants were seen as the first colonisers of land, but new research reveals that fungi ruled terrestrial ecosystems long before plants took root. Emerging hundreds of millions of years earlier, fungi played a crucial role in shaping early environments, forming partnerships with algae and recycling nutrients to build proto-soils. Their activity stabilised surfaces, released essential elements like phosphorus, and prepared land for the eventual arrival of plants. By acting as the planet’s original ecosystem engineers, fungi created the foundations that allowed terrestrial life to flourish. This discovery reshapes our understanding of Earth’s evolutionary history, showing that the rise of forests and land plants was not a sudden event but a continuation of the ecosystems fungi had already been cultivating for eons.

Fungi led the way on land, preparing the world for plants

Fungi didn’t wait for plants to conquer land—they did so on their own evolutionary schedule. Recent studies led by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), in collaboration with researchers worldwide, have reconstructed the deep evolutionary history of fungi using advanced genetic techniques. These findings suggest that ancient fungi were not merely passive organisms but actively influenced the formation of the earliest terrestrial ecosystems, creating conditions that would later allow plants to thrive.As study published in Nature, “Complex multicellular life—organisms composed of many cooperating cells with specialised roles—evolved independently in five major groups: animals, land plants, fungi, red algae, and brown algae,” explains Gergely Szöllősi, co-author and head of the Model-Based Evolutionary Genomics Unit at OIST.This independent emergence of complexity in multiple lineages marks one of the most significant evolutionary transitions on Earth. Understanding when each group appeared is crucial for reconstructing the history of life, revealing which organisms set the stage for others. Unlike a single dramatic event, the evolution of complex life unfolded repeatedly across different lineages, with fungi being among the earliest innovators.

How scientists use genetics to uncover their evolutionary history

Fungi are notoriously difficult to date. Unlike plants and animals, whose fossil records provide relatively reliable anchors, fungal bodies are soft and filamentous, rarely leaving fossils behind. Additionally, fungi evolved complex multicellular structures multiple times, unlike animals and plants, which tend to show a single origin of complex forms.Because traditional fossil records are sparse, researchers turn to molecular clocks. By comparing genetic sequences, scientists can estimate relative evolutionary timelines. However, molecular clocks require careful calibration to convert relative differences into absolute ages in years—a challenge compounded by the patchy fossil record.

Fungal evolution revealed: How horizontal gene transfers uncover their ancient history

To overcome these obstacles, the OIST team employed an innovative approach: analysing rare horizontal gene transfers (HGT) between fungal lineages. Normally, genes are passed down vertically from parent to offspring. In HGT, however, genes jump “sideways” between unrelated species. These gene swaps serve as precise temporal markers: if a gene moves from lineage A to lineage B, lineage A must predate lineage B.Using this method, the researchers identified 17 robust gene transfer events. When combined with the few reliable fungal fossils, these data allowed the team to refine the timing of key branching points in fungal evolution, providing a clearer picture of their deep history.

How ancient fungi shaped ecosystems long before land plants appeared

The results indicate that the common ancestor of all living fungi existed between approximately 1.4 and 0.9 billion years ago, well before the first land plants appeared around 470 million years ago. During this long prelude, fungi likely diversified in aquatic environments and along damp shorelines, forming partnerships with algae in early microbial communities.“Fungi run ecosystems—recycling nutrients, forming symbiotic relationships, and sometimes causing disease,” says Lénárd Szánthó, co-first author of the study. “Pinpointing their timeline shows that fungi were already experimenting with ecological roles long before plants arrived, creating the foundations for terrestrial life.” Fungi are chemical wizards of nature. By weathering rock, releasing phosphorus, and transferring nutrients through their extensive networks, they gradually created proto-soils. These processes likely softened harsh terrestrial environments, reducing the barriers for plant colonisation.If coastal rocks and wet continental surfaces were already inhabited by fungi and algae, early plants may have found an environment preconditioned for life. Fungi’s nutrient cycling and surface stabilisation effectively prepared the land, setting the stage for the dramatic expansion of plants millions of years later.