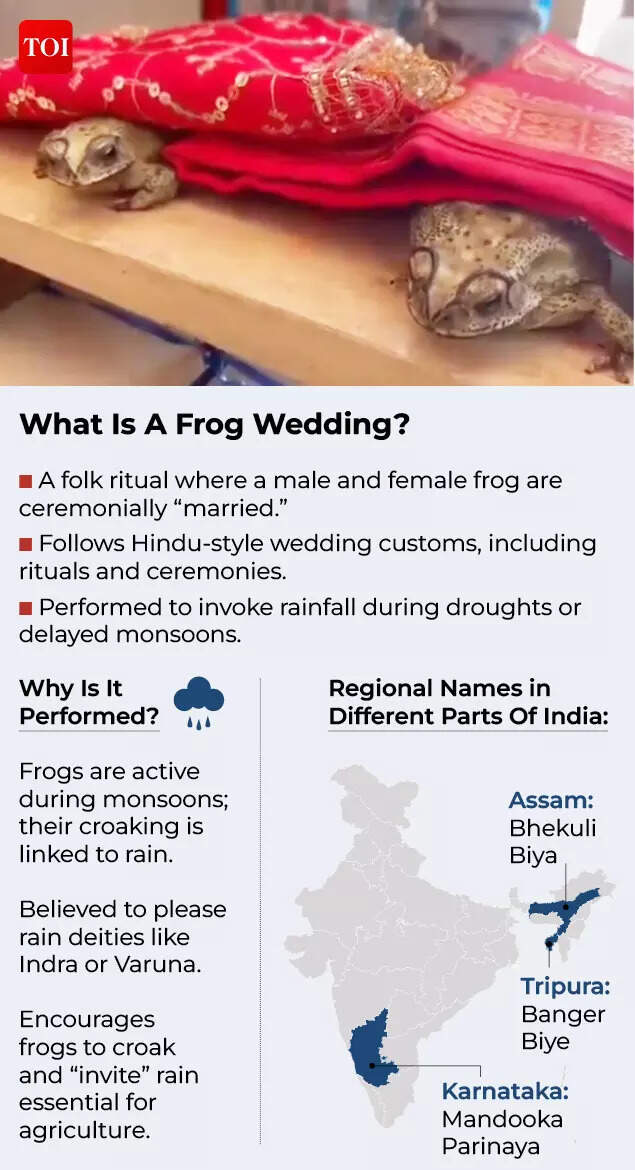

For generations, they have lived quietly at the edge of ponds, paddy fields, and village lore—small, croaking creatures whose voices rise just before the skies open. To meteorologists, frogs are bioindicators. To farmers staring at cracked earth and empty canals, they are something more.In villages across India, when the monsoon fails and prayers go unanswered, hope takes an unusual shape.It is dressed in miniature wedding clothes.It is blessed with turmeric, vermilion, and mantras.And it is sealed not by humans—but by frogs.This is the story of India’s frog weddings—rituals born of drought, fear, faith, and an intimate relationship with nature. From Assam’s exuberant Bhekuli Biya to Karnataka’s solemn Mandooka Parinaya, these ceremonies reveal how communities confront climate uncertainty not with data charts, but with song, symbolism, and collective belief.What Is A Frog Wedding And Why Is It Performed?A frog wedding is a folk ritual in which a male frog and a female frog are ceremonially “married” following Hindu-style wedding customs. The primary purpose is to invoke rainfall during prolonged dry spells, droughts, or delayed monsoons.Frogs are closely associated with rain because they become most active during the monsoon—their mating season—when they croak loudly and breed in newly formed water bodies. Villagers believe that marrying frogs encourages them to croak joyfully, appeases rain deities such as Indra or Varuna, and invites rain essential for agriculture.The ritual is not prescribed in ancient Hindu scriptures like the Vedas or Puranas. Instead, it is a folk custom, shaped by indigenous tribal beliefs, agrarian anxieties, and local Hindu practices, reflecting a deep emotional bond with nature.How Old Is This Tradition?The frog wedding ritual is believed to have originated in Northeast India, particularly Assam, and later spread to states such as Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and Karnataka.It is a very old oral tradition, passed down through generations rather than recorded in religious texts. Although the Sanskrit word manduka means frog (as seen in the Mandukya Upanishad), no frog wedding is mentioned there.Scholars suggest the practice is several centuries old, dating back to pre-British times when monsoon failures posed existential threats to farming communities. Folklore studies from the 1990s document it as part of traditional Assamese culture, with some tracing its roots to ancient tribal belief systems of the Northeast.The ritual continues today. In Assam alone, frog weddings were reported in 2023, 2024, and 2025 in districts such as Kamrup, Biswanath, and Darrang—demonstrating how age-old customs persist as coping mechanisms amid changing climate patterns.

Where Did The Frog Wedding Ritual First Take Shape?The ritual is widely believed to have originated in Assam, where it is known as Bhekuli Biya.Its emergence is linked to animistic beliefs and agrarian life, where communities dependent on monsoon rains developed symbolic rituals to cope with drought and delayed rainfall. Observing that frogs croak intensely during the rainy season, villagers associated their mating with the arrival of rain.Socially, the ritual arose in weather-dependent rural societies facing water scarcity. It blends local superstitions with Hindu rites, offering communities emotional relief, collective hope, and a sense of control during harsh dry periods.From Assam, the practice gradually spread to northern, central, and western India—adapting to similar environmental anxieties in regions such as Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Karnataka.

How Do Frog Wedding Rituals Change Across Different Regions?The basic steps remain the same: villagers catch a male and a female frog, conduct a wedding ceremony with prayers (puja), mantras, and offerings, dress the frogs, and then release them into water. However, the style, scale, and details vary according to local customs.Assam (Bhekuli Biya):The ceremony is lively and elaborate, resembling a full Assamese wedding. Frogs are cleaned with turmeric and mah dal paste, rubbed with oil, bathed, and dressed in traditional Assamese clothes and jewellery. They are placed on a platform, tied with a red thread, and vermilion (sindoor) is applied to the female frog. A priest performs prayers to rain gods such as Varuna. The entire village participates with band parties, dhuliya (drummers), dances, food, and a procession similar to a groom’s party. Afterward, the frogs are released into a pond. If they remain together, it is believed rain will come soon.Songs sung during Bhekulir Biya form an important genre of Assamese folk literature. These songs have no specific author or composer and have been passed down orally from generation to generation since time immemorial.Uttar Pradesh (Varanasi, Gorakhpur):The ritual follows traditional Vedic Hindu customs and is often conducted in temples such as the Kalibari temple. Priests chant mantras, sindoor is applied, and the ceremony is performed seriously by community groups, especially during intense heat or drought.Karnataka (Mandooka Parinaya):The ceremony is calmer and more prayer-focused. Frogs are often named Varuna (male, water god) and Varsha (female, rain). They are bathed in turmeric water, dressed in special clothes, and adorned with symbols such as toe rings. The ritual takes place in temples or community spaces decorated with flowers and small pandals, with less festivity than in Assam.Madhya Pradesh:In some cases, clay or toy frogs are used to avoid harming live animals. Prayers are offered to Indra. In one instance in Bhopal in 2019, a symbolic “frog divorce” was performed after excessive rainfall followed the wedding.Tripura (Banger Biye):Similar to Assam’s version but influenced by local tribal and tea-garden traditions, including garlands and the application of sindoor.Overall, rituals in the northeast and north tend to be more vibrant, with songs, food, and dances, while southern versions are quieter and more symbolic. The practice reflects a blend of tribal beliefs and Hindu traditions shaped by dependence on rainfall for agriculture. It is generally viewed as a belief or superstition, with no scientific proof—rain follows seasonal patterns, and frog activity coincides with moisture levels.Other places: Occasionally observed in Bihar (such as Saharsa), West Bengal (Nadia district), and rarely in parts of Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, or hilly regions.The ritual does not occur everywhere in these states. It is usually performed only in small rural villages when rainfall is scarce and farming is affected.

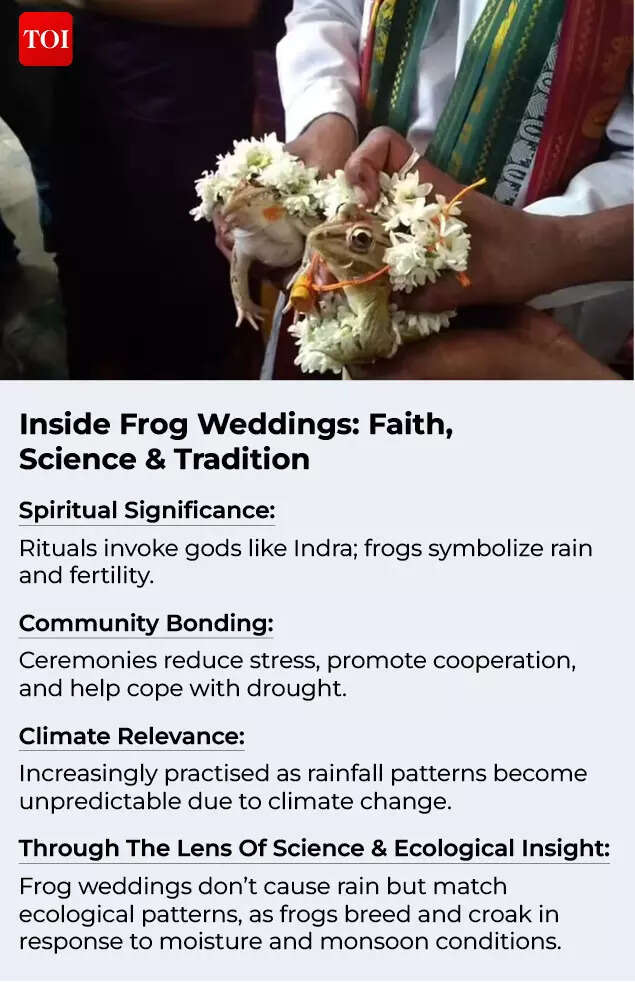

Faith, Science, And Tradition: How Assam’s Frog Weddings Are Interpreted TodayInterpreting traditional rain-invocation rituals like Assam’s Bhekulir Biya does not require choosing only one perspective. These practices are layered and meaningful, and a balanced understanding can draw from faith, science, and cultural heritage, especially in a world affected by climate change.From a faith-based perspective, frog weddings are expressions of spiritual belief and connection with divine or natural forces. In agrarian communities, frogs symbolise fertility and rain due to their link with water and monsoons. The ritual is an act of devotion, invoking Hindu gods like Indra or local deities. Even today, faith offers comfort during droughts, reinforcing moral and cosmic harmony and providing hope and resilience.Scientifically, these rituals do not cause rain, but they align with ecological patterns. Frogs breed and croak in response to humidity and rainfall, acting as bioindicators. Anthropology and psychology show that such communal rituals reduce stress, strengthen cooperation, and help communities cope with drought. In this sense, they can be seen as early, observation-based responses to weather variability.As cultural heritage, frog weddings preserve folklore, music (such as biya-naam songs), and community traditions passed down for generations. In Assam, they reinforce identity and continuity at a time when urbanisation and globalisation threaten traditional practices. Anthropologists and institutions like UNESCO recognise such rain rituals as intangible cultural heritage that supports resilience and respect for nature’s cycles.Ultimately, an integrative interpretation works best: faith provides emotional depth, science offers explanation, and cultural heritage ensures continuity. In regions like Assam, dismissing these rituals as “mere superstition” overlooks their role in social cohesion and well-being.Reports also suggest that rituals like Bhekulir Biya (frog weddings) in Assam have become more frequent in recent years, as climate change has made rainfall patterns increasingly unpredictable.Frog Weddings: Nature As Observed By CommunitiesThe practice of Bhekulir Biya in Assam reveals how historical agrarian communities understood and engaged with nature and climate.Keen Observation Of Ecological CuesVillagers noticed that frogs croak vigorously during their mating season, coinciding with the monsoon. Folklore reflects this, such as an Assamese verse where clouds say rain will come only when frogs croak. By ritually “marrying” frogs, communities symbolically encouraged this natural signal, demonstrating ecological wisdom and using amphibians as bio-indicators long before modern meteorology.Animistic And Interdependent WorldviewNature was seen as alive and relational. Frogs symbolized water, fertility, and abundance, acting as intermediaries to rain deities. Dressing frogs in miniature wedding attire, applying vermilion and turmeric, and performing priest-led ceremonies reflected a belief that human actions could harmonize cosmic forces. Agriculture, weather, and human welfare were viewed as interconnected.Cultural Adaptation To Climate VulnerabilityIn monsoon-dependent regions like Assam, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh, delayed rains caused drought and crop failure. Frog weddings served as a cultural coping mechanism—offering psychological comfort, reinforcing community solidarity through songs, feasts, and collective participation. Symbolic “divorces” during excessive rainfall show adaptability to real-time weather changes.Faith, Folklore, And HopeThese rituals combine respect for nature with human dependence on it. Even amid modern climate challenges, frog weddings persist, preserving cultural memory and teaching resilience and harmony.Songs Of Bhekulir BiyaTraditional songs, often called Bhekuli Biyar Geet or Biya Naam, are sung collectively, mostly by women, in lively, repetitive styles that mimic human weddings. They praise frogs as rain-bringers, invoke rainfall, and blend humour, devotion, and pleas to agricultural deities. Orally transmitted, these songs vary regionally, with motifs like frog croaks (tor tor), dhol beats, and calls for rain to fill paddy fields.

Chhattisgarh: Tribal Frog Wedding Held To Appease Rain GodAn unusual wedding took place in a remote village of Chhattisgarh’s Surajpur district in August last year—not between humans, but between two frogs. The ceremony, steeped in centuries-old tribal belief, was performed to appease the Rain God as monsoon clouds remained elusive over the region.The male and female frogs were adorned in miniature bridal attire, and their union was solemnised with rituals identical to a human marriage. The ceremony included dance, a wedding procession, music, and the beating of traditional drums.Villagers from Dhondha and neighbouring hamlets thronged the venue, dancing and singing in celebration. Women performed the main rituals and sang folk songs. In videos from the event, tribal women can be seen dressed for wedding ceremonies, holding frogs in covered copper vessels while singing and dancing.Among the Gond and Oraon tribal communities of Chhattisgarh, such ceremonies are rooted in the belief that marrying frogs can invoke the God of rain to bless parched fields.“When the skies remain dry, we turn to our deities in the ways our ancestors taught us,” said village elder Ramesh Kerketta. “The frog wedding is symbolic, it’s nature calling to nature to save us from drought and bring rain.”Dozens participated in the ceremony, treating it with religious reverence and festive enthusiasm. The frog couple, bound in a sacred “pact of rain,” was later released into a nearby pond, symbolising the union’s connection with water.Such rain-invoking rituals are still practised across rural Chhattisgarh, reflecting the deep intertwining of tribal cosmology, agrarian life, and seasonal rhythms. While meteorologists forecast scattered showers later that week, villagers said the frog wedding had already lifted spirits and raised hopes of rainfall.Speaking to TOI, prominent tribal leader and former Union minister Arvind Netam said,“Tribal communities have a rain God of their own, whom they call upon through weddings of frogs. It happens in almost all tribal-dominated villages and is part of several traditions directly related to nature.”He added that these rituals remain integral to tribal life.“Be it trees, forests, woods, land, river, everything is worshipped by tribals without any interference of any other religion.”Karnataka: Frog Wedding Held As Monsoon Delay Halts FarmingIn June 2023, residents of Surashettikoppa village in Kalghatgi taluk of Dharwad district, Karnataka, conducted a frog wedding after the delayed monsoon dried up water bodies and brought agricultural activity to a standstill.To appease the Rain God, villagers organised the wedding of a pair of frogs—a practice followed in several parts of North Karnataka whenever monsoon delays or drought-like conditions prevail. In some villages, people also conduct donkey weddings.The villagers decorated the local Brahmalingeshwara temple with flowers, buntings, and festoons. All customary wedding rituals were performed, including pujas, a pandal, and other local traditions. The frog couple was married inside the temple in the presence of villagers.Kubergowda Nagangowda Murali, a folk artist and villager, said enthusiastic participation ensured the ceremony’s success. After the wedding, a mass feeding was organised.“A few years back, we faced a drought-like situation and held a frog wedding. After a few days, we received rainfall. We are supposed to be busy with agricultural activities at this time, but due to the lack of rain, agricultural activities have stopped. So, we decided to perform a frog wedding once again in the hope of rain,” he said.Gangangowda Naduvinmani, a GP member, added, “We sowed maize last week, but there has been no rain. If there are no rains in the next few days, we are likely to face drought. As our elders suggested that we marry a pair of frogs, we did so.”‘Manduka Kalyanotsava’ Performed Amid Drinking Water CrisisWith pre-monsoon showers absent and the southwest monsoon reaching Kerala nearly 10 days late, residents of Udupi held a frog wedding in June 2019 to propitiate the Rain God.The ‘Manduka Kalyanotsava’ saw frogs named ‘Varuna’ and ‘Varsha’ enter wedlock during the auspicious Simha Lagna. The ceremony was preceded by an elaborate reception beginning at Maruthi Veethika and ending at Hotel Kidiyoor, with a procession passing through Kavi Muddana Marg and Old Diana Circle.Organised by Udupi Zilla Nagarika Samiti Trust and Pancharatna Trust, the frogs—brought from Kelinje and Kalsanka—were transported in a cycle rickshaw. Women from Matru Mandali and Bhajana Mandali initiated the rituals, while Chitpadi Nasik Band provided ceremonial music.After the priest solemnised the marriage, the couple was returned to the cage. Janardhan Sherigar hosted lunch for guests, and later the frogs were released into Mannapalla lake.“Four frogs were brought in, and a zoologist’s help was sought to pick ‘Varuna’ and ‘Varsha’, a male and a female. We organised this ritual because Udupi is facing acute drinking water shortage and hope it ends soon,” said Nithyananda Olakadu, general secretary of Nagarika Samiti.Social worker Tharanath Mestha said, “This kalyanotsava was organised as per Hindu rituals. Despite criticism, we are doing this for betterment of society and for rain.”

Frog ‘Divorce’ Performed After Excess RainfallIn September 2019, a frog couple married two months earlier to bring rain was symbolically ‘divorced’ in Bhopal after incessant rainfall caused widespread flooding across Madhya Pradesh.The original frogs, married in mid-July during a dry spell, could not be found. Organisers therefore created two clay frog models and performed the divorce ritual in a temple.“It is believed that getting a male and female frog married brings rain as Indra Dev sends his blessings. Till mid-July, the state was facing a dry spell and people were suffering, so we decided to perform the ‘totka’. Bhopal had rain the very next day,” said Rinku Bateja, secretary of the Mandal.But the rain did not stop.“Now, the heavy rain has started causing a lot of problems and there is flooding in many parts of the state. So, our priest suggested that we separate the two,” Bateja said.Unable to locate the frogs, the Mandal used oversized clay models.“As Madhya Pradesh has received more than enough rain, we decided to follow the priest’s advice and performed a ceremony to separate the frogs. We sent the female back to her ‘maternal home’ and then immersed the two clay-frogs in separate vessels filled with rainwater,” he said.

Why Frog Weddings Still Matter In An Age of Climate Change?Speaking to TOI, Dr Dipankar Thakuria, a folklore researcher and environmental activist, said frog weddings must be viewed through the twin lenses of cultural memory and ecological understanding. | Expert ViewQ: What is Bhekulir Biya, and why is it practiced in Assam?A: Bhekulir Biya, or the frog wedding, is a traditional rain-invocation ritual practiced mainly in rural Assam during periods of low or delayed rainfall. It is deeply rooted in agrarian life, where farming depends almost entirely on timely monsoons. The ritual symbolises a community’s collective appeal to rain gods and natural forces for survival.Q: Many see frog weddings as superstition. How should they really be understood?A: Viewing frog weddings only as superstition misses their deeper cultural and social meaning. These rituals evolved from generations of close observation of nature. Frogs are strongly associated with water, humidity, and monsoons, so they became natural symbols of rainfall and fertility. The ritual also provides emotional reassurance and strengthens community bonds during times of environmental stress.Q: Is there any ecological logic behind associating frogs with rain?A: Yes, there is a clear ecological connection. Frogs are highly sensitive to moisture and rainfall. Their breeding and croaking increase with rising humidity and the onset of monsoons. Communities noticed these patterns long before modern science explained them. While frogs do not cause rain, their behaviour often signals changing environmental conditions.Q: How does modern science view such rituals today?A: Scientifically, these rituals do not influence weather. However, ecology and anthropology show that they reflect early, observation-based responses to climate variability. Communal rituals like these also reduce stress, encourage cooperation, and help people cope with drought—benefits that are very real, even if the ritual itself does not produce rain.Q: Are frog weddings still being performed today?A: Yes. In rural Assam, frog weddings continue to be performed, especially during severe dry spells. Reports suggest that they have become more frequent in recent years as rainfall patterns have grown increasingly unpredictable due to climate change.Q: Are these rituals changing with time?A: They are evolving. In some places, frog weddings have become more symbolic or heritage-focused, and sometimes they attract media attention. However, in many villages, the ritual still carries genuine meaning and is performed only when rain is urgently needed.Q: Will rituals like Bhekulir Biya survive in the future?A: I believe they will survive, though in adapted forms. As long as rural communities remain dependent on rainfall and face climate uncertainty, such rituals will continue to serve as cultural lifelines—connecting people to nature, shared memory, and collective resilience.