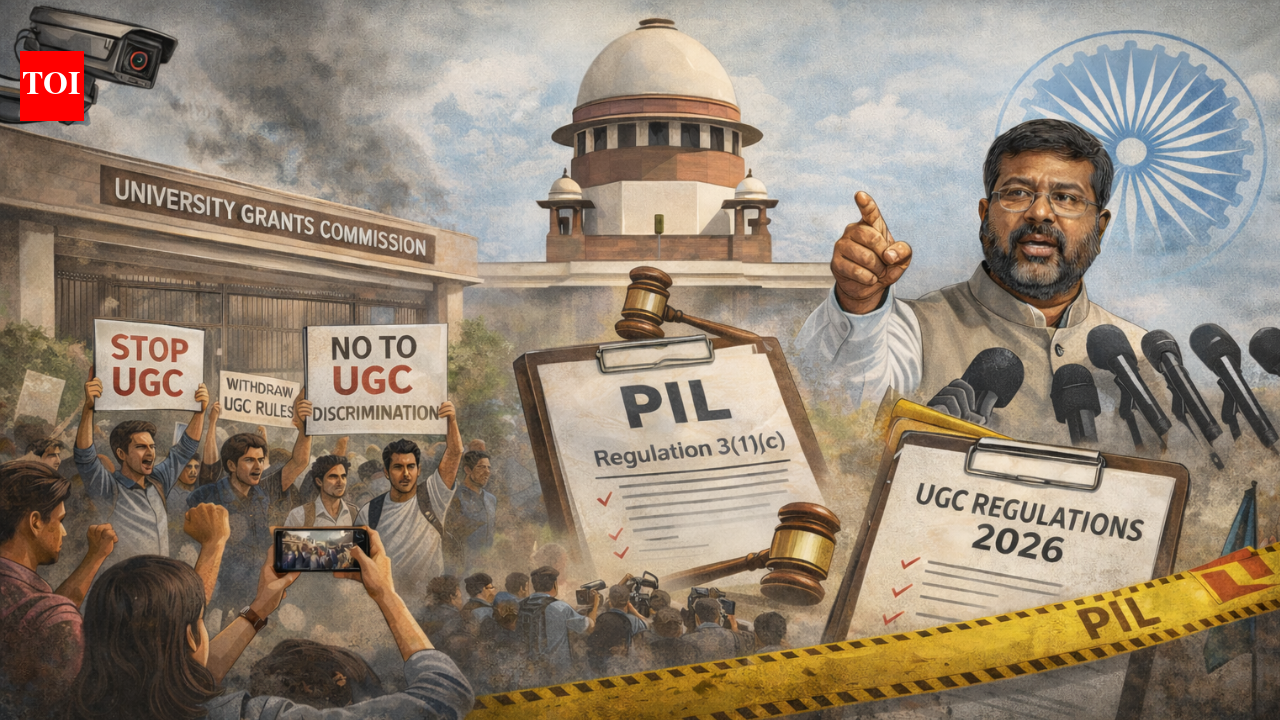

Caste is the one Indian subject that never stays in the classroom; it travels with the student, the teacher, the institution—and, sooner or later, the regulator. On January 13, the University Grants Commission (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations, 2026 arrived as the UGC’s attempt to turn that lived reality into enforceable campus governance—explicitly foregrounding discrimination faced by Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) and Other Backward Classes (OBC). The rulebook came with the full compliance kit: Equal Opportunity Centres and equity committees with mandated representation, a 24×7 helpline, tight inquiry timelines, and “Equity Squads” tasked to “maintain vigil”. And then, almost on cue, the backlash organised itself. Students gathered outside the UGC office in Delhi warning of surveillance and misuse; resignations and political criticism recast the regulations as overreach; and a Supreme Court PIL challenged Regulation 3(1)(c)—the clause defining caste-based discrimination as discrimination against SC/ST/OBC members—as “non-inclusionary”. Online, the argument has moved faster than the clarifications, turning a regulatory document into a live national quarrel over equity, due process and who the law is written for.

UGC’s 2026 equity rules: What they define, build, enforce and leave hanging

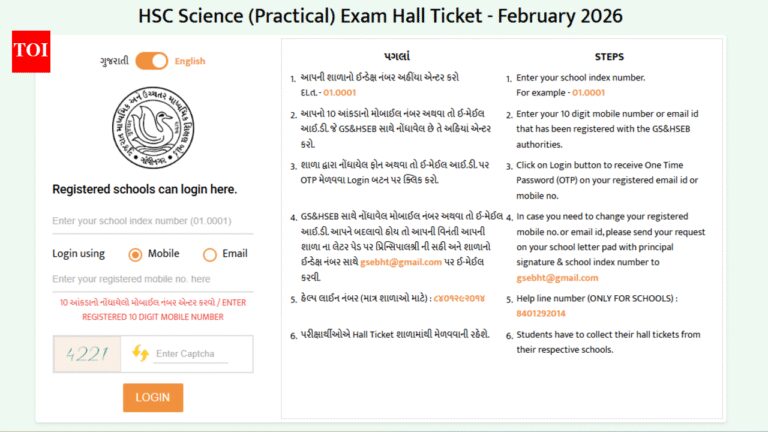

The UGC (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations, 2026 draw three sharp boundaries. First, they define the problem broadly: Discrimination includes any unfair, differential or biased treatment—explicit or implicit—on grounds of religion, race, caste, gender, place of birth, disability, and acts that impair equality of treatment or impose conditions incompatible with human dignity. Second, they define “caste-based discrimination” narrowly: Discrimination on the basis of caste or tribe against members of SC, ST and OBC. In other words, the regulations speak the language of universal rights, then anchor caste injury to a historically specific victim-set—one reason the clause has become litigious. Third, they define the complainant class widely: An ‘aggrieved person’ is anyone with a complaint connected to grievances under the regulations, and “stakeholders” include students, faculty, staff, management, and the head of the institution. What the 2026 rules propose is not merely a complaint channel; it is an institutional nervous system. Every HEI must build an Equal Opportunity Centre tasked with implementation, guidance and diversity-building. The EOC is backed by an Equity Committee with mandated representation of OBC, persons with disabilities, SC, ST and women.A 24×7 Equity Helpline is compulsory, with confidentiality on request. The procedure is designed to move like a fire drill: The committee meets within 24 hours, reports in 15 working days, and the head initiates action in 7 working days, with an appeal route to the Ombudsperson.What it does, in effect, is convert equity into compliance: Biannual public reporting, UGC monitoring, and penalties that can hurt institutions where it matters—funding access, programme permissions, recognition.And what it does not do is the source of much of the anger: It does not explicitly spell out standards of proof, it does not promise symmetry for reputational harm, and it does not build a visible deterrent for malicious complaints. The state is saying: trust the architecture. Parts of the campus are replying: we don’t trust who gets to operate it.

Why are students pushing back? Fear of being the accused

A regulation can be drafted like a disinfectant—meant to cleanse a system—but once released, it also stings every open wound it touches. According to a PTI report, New Delhi has now become one theatre of that sting: Students from upper-caste communities have called for a protest outside the University Grants Commission headquarters on Tuesday, warning that the new UGC Regulations, 2026 could lead to chaos on campuses.The protest call urges students to rally under the slogan “No to UGC discrimination”—a neat reversal that tells you what the backlash is really about. It’s not whether discrimination exists, but whether the cure is being designed in a way that can be turned into a weapon. The rules have drawn criticism from general category students who fear the framework could end up discriminating against them.The friction points, as students are framing them, are less about the morality of equity and more about the mechanics of accusation.Delhi University PhD student Alokit Tripathi told PTI that the new rules would create “complete chaos” because the burden of proof would be shifted to the accused, with no safeguards for those wrongly accused. Then he sharpened the charge into a moral verdict. “The new regulations are draconian in nature. The definition of victim is already predetermined. Victim can be anyone in the campus,” Tripathi said. The anxiety is not only about outcomes; it is about atmosphere—an ecosystem where suspicion can become ambient. Pointing to the surveillance concern that has travelled far beyond clause numbers, he added, “With the proposed Equity squads, it will be akin to living under constant surveillance inside the campus.”The argument is already spilling out of Delhi. In Lucknow, too, students at Lucknow University staged a protest against the same UGC regulations; in a PTI video from the campus, demonstrators said the rules notified on January 13 have triggered widespread concern among students, who fear the measures could be misused and result in unequal treatment.The Lucknow protest carries the same anxiety in fewer words: that a policy meant to protect the vulnerable may also produce new resentments and new targets—an early indication that this is travelling beyond Delhi into a broader student flashpoint.

A Supreme Court PIL: How one line in UGC’s rules sparked a court fight

A PIL in the Supreme Court has put the spotlight on one clause in UGC’s 2026 regulations—Regulation 3(1)(c)—and asked a straight question: can an anti-discrimination framework define caste discrimination in a way that narrows who can be recognised as a victim?The clause at the centre of the petition defines ‘caste-based discrimination’ as discrimination “only on the basis of caste or tribe” against members of Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) and Other Backward Classes (OBC).The petition argues this makes the definition non-inclusionary and creates a hierarchy of protection—because it restricts caste-based discrimination, as a category, to specific groups.Why does that matter on campuses? Because the 2026 regulations are not just a statement of intent; they build a grievance system. Institutions are required to run Equal Opportunity Centres, set up committees, operate a 24×7 Equity Helpline, and provide an appeal route through an Ombudsperson. The PIL’s concern is that once “caste-based discrimination” is defined through a protected-category filter, students and staff outside SC/ST/OBC groups may be left with a narrower form of recognition: they may complain of “discrimination” generally, but not claim “caste-based discrimination” as defined—potentially affecting how their complaints are processed within this architecture.The petition invokes Articles 14, 15(1) and 21. It asks the court to pause enforcement of Regulation 3(1)(c) “in its current form” until it is reviewed, and to keep grievance mechanisms accessible to all in the interim. The outcome will travel beyond the courtroom: it will decide whether UGC’s definition is seen as a historically grounded safeguard—or a classification that limits equal access to redress.

No misuse will be allowed: Education Minister

As the controversy jumped from campus gates to a Supreme Court file, the Centre moved quickly to occupy the one ground that both sides were fighting over: Misuse. Addressing reporters, Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan offered a blanket assurance that the regulations will not be weaponised, and that enforcement will stay within constitutional limits. “I would like to assure everyone that no misuse of the law in the name of discrimination will be allowed. Ensuring this is the responsibility of the UGC, the Government of India, and state governments. All actions will be carried out within the ambit of the Constitution. This matter is also under the supervision of the Supreme Court, and I assure you that there will be no discrimination,” Pradhan said. The second part of the government’s response is less rhetorical and more logistical: clarification, soon. Media reports say the Ministry of Education is preparing to put out clearer public messaging to counter what it describes as confusion and online backlash around the 2026 regulations.

The real test is trust

India does not lack laws; it lacks laws that people trust. The UGC’s 2026 regulations are an attempt to force institutions to stop looking away from discrimination. The pushback is an attempt to stop the remedy from becoming another instrument of power. Both impulses are recognisably Indian, and both are, in their own way, right. The question is whether the UGC can write a system that protects without presuming, punishes without prejudging, and listens without surrendering. If it cannot, we will return to our national comfort zone: outrage, retreat, and the quiet continuation of the thing we claimed we were fixing.