When Rukmini boarded the flight to Delhi from Kolkata, it was the first time she had ever travelled to Delhi. It was her first flight, and only the second city she had seen outside her village. Hailing from a small village near Kalna in Bengal, Rukmini had spent most of her life seated on the floor of her home, bent over fabric, stitching kantha embroidery onto sarees. The work brought in a few hundred rupees at a time—barely enough to support her ailing mother and younger sister. It was not a profession she had chosen, but one she had inherited, passed down quietly from one generation of women to the next. So when India Silk House Agencies asked her to come to Delhi to showcase her work, the invitation arrived as both surprise and fear. Delhi was far away, unfamiliar, and intimidating. Yet the company offering her this opportunity was not unknown. Founded in 1971, Indian Silk House Agencies had been working with weavers and artisans across Bengal for decades. In her village, the name carried a sense of trust—almost sacred familiarity—earned over years of consistent engagement and fair dealings.

Rukmini travelled to Delhi with two other girls from her village to present her work as an artist at a showcase at Omaxe Mall, Chandni Chowk. It was a moment she had never imagined. For the first time in her life, she was not invisible. People asked for her photograph. They asked her about her stitches, her motifs, her process. In that moment, she realised something quietly profound—that perhaps the time for “artists” and “kalakars” like her had finally arrived.The silent language of KanthaFor those unfamiliar with it, kantha is one of India’s oldest forms of embroidery, traditionally done using a simple running stitch. Born in the households of Bengal, it began as a way for women to recycle worn cotton saris into layered quilts, embedding personal stories through motifs and patterns. Aari work, on the other hand, uses a hooked needle to create chain stitches and is practised by specialised artisan groups. In contemporary textile traditions, especially in regions like Murshidabad and Nadia, the two techniques often come together—kantha’s narrative softness meeting aari’s ornamental precision. What unites these crafts is not machinery, but memory. The knowledge is hereditary, passed down through observation rather than instruction, mostly within homes. Young girls learn by watching older women stitch late into the night, after the day’s chores are done. There are no certificates, no formal recognition—only skill refined over decades. Rukmini was one of thousands of such women whose labour quietly fed India’s handloom economy without ever being named.

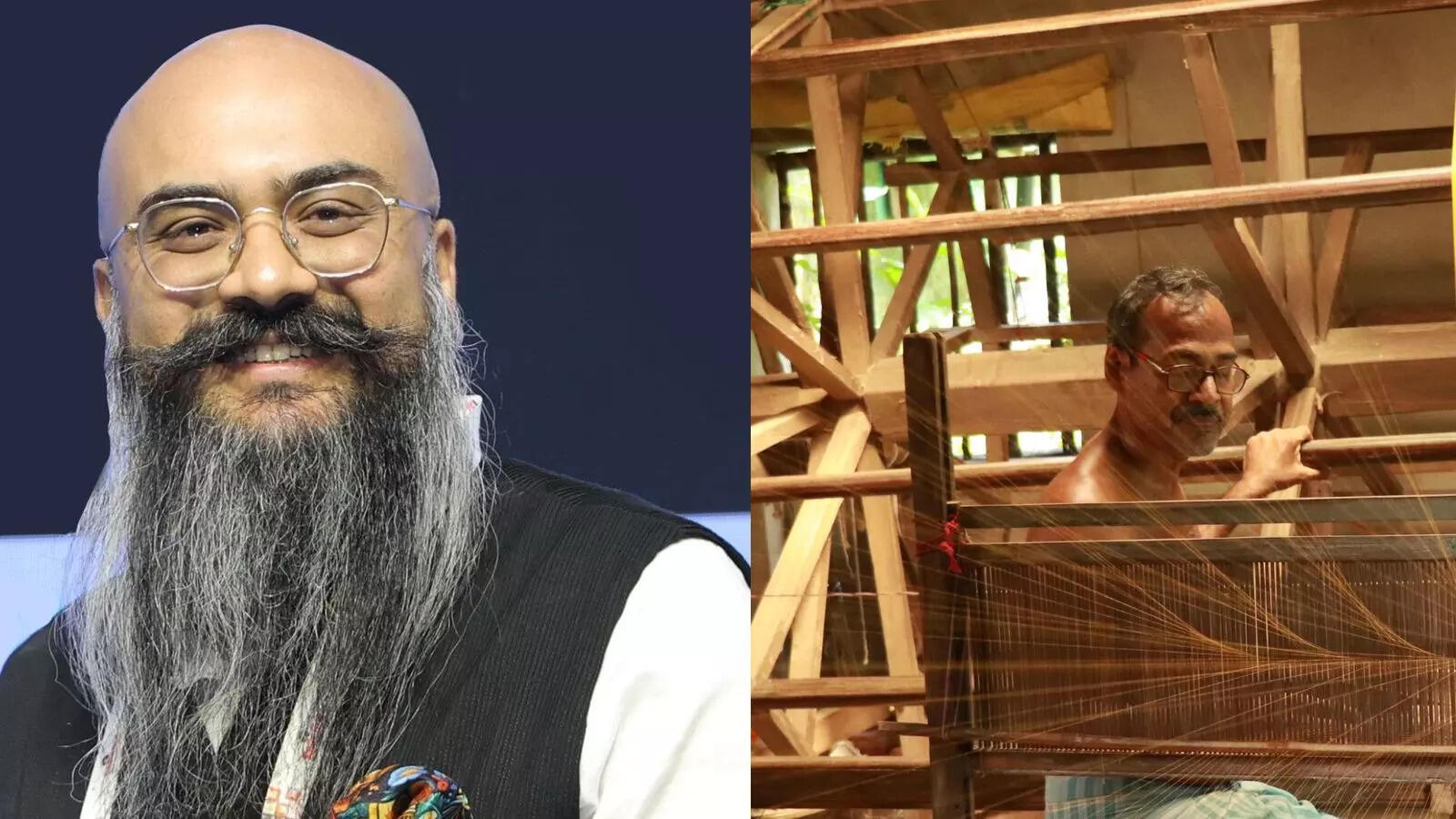

A quiet revolution in the saree industryIndian Silk House Agencies has, over the years, brought about a quiet but consequential shift—elevating weavers and artisans from anonymous suppliers to acknowledged artists. For many outside Kolkata, the name may not be instantly familiar. But within Bengal’s textile ecosystem, it is a legacy institution. Formally founded in 1971 by Sri Sumati Chand Samsukha in North Kolkata, the brand began as a saree store committed to promoting local artisans. Its founding philosophy was simple yet radical for its time: high-quality, authentic, pure silk sarees should be accessible and affordable to Indian women. In 1998, the founder’s daughter, Pratibha Dudhoria, took over the reins, significantly expanding the brand’s retail presence across West Bengal. Today, under the leadership of CEO Darshan Dudhoria, India Silk House Agencies is making a quiet contribution towards uplifting the plight of weavers.

Lessons from Banaras: A legacy of fairnessEvery legacy begins somewhere. For Indian Silk House Agencies, that beginning was not in a retail space, but in Banaras—amid looms, weavers, and quiet transactions rooted in trust. “We had a house in Banaras, and in those days our work didn’t begin in an office. It began from the villages, on the looms, in the hands of the weavers, and finally, it arrived at our home. My father knew exactly what customers wanted. If someone asked for a certain colour, a particular weave, a specific pattern, he would pass it on clearly, patiently, like he was giving the weavers a promise to fulfil. Then we would wait. A week later, before the sun was properly up, they would come. Then the box would be opened. My father would examine every piece right there in front of them. Each piece was given the respect like a fine piece of art. Right there, on the spot, he would pay them. Not later. Not next week. Immediately. It was like giving an immediate validation to creativity. And there was one more rule in our house: once the box came in, nobody touched it casually. No one. Those pieces weren’t “stock.” They were a week of someone’s life, long hours, tired eyes, practiced hands, and my father made sure everyone understood that without needing to explain it.” says Pratibha Dudhoria, remembering her father fondly.

What Indian Silk House Agencies does differentlyToday, Indian Silk House Agencies works with over 15,000 artisans across India. Every pure silk saree sold comes with a certificate of authenticity that details where it was made, who made it, and the nature of the silk and weave. The saree is not just a garment—it is a documented piece of art. Soon, each saree will also carry a QR code, allowing customers to see a video of the weaver who made it. This level of transparency is rare in an industry where anonymity has long been the norm. The impact of this approach is already visible. In Banaras, there is evidence of reverse migration. Weavers who once left home to work in textile mills in Surat are returning, drawn back by renewed demand for authentic handloom sarees. This, according to the company, is one of its most meaningful achievements.Taking the saree to the peopleRetail, for Indian Silk Agencies, has never been confined to fixed locations. For nine months of the year, over two consecutive years, the company has operated travelling exhibitions—loading nearly 3,000 sarees into trucks and taking them from city to city, every single weekend. From Maharashtra to Rajasthan, from Nashik and Pune to Tirupati and Kolhapur, these exhibitions bring handloom directly to consumers. There are now two parallel trucks operating simultaneously in different parts of the country. This model is helping spread awareness about regional craft across India. Women at the centre of craftSustainability, for the brand, extends beyond materials into community development and artisan empowerment—especially women. In villages like Jiaganj in Murshidabad, women play a central role in kantha and hand-stitch work. While men often operate foot looms for weaves like Baluchari, the intricate hand embroidery is predominantly done by women. Similar communities exist across Shantiniketan, Murshidabad, Arni, Coimbatore, and Mubarakpur near Banaras. In many of these places, rising demand is drawing people back into traditional crafts. The cycle is complex and often ironic—artisans once left handloom to operate machines producing imitation sarees, only to return years later to revive the very craft those machines copied. Indian Silk House Agencies’ effort lies in strengthening this supply chain and ensuring artisans are connected directly to markets that value their work.

Understanding the scale of the saree economyAccording to Darshan, the 3rd generation scion who has made it a mission to bring back saree and its invisible artisans on the global map, “To put things in perspective, India’s saree industry is valued at approximately ₹80,000 crore. Yet, despite its scale, the human labour behind sarees often remains undervalued. By recognising artisans as artists, documenting their work, and placing them at the centre of the narrative, we are attempting to correct that imbalance.“A stitch that travelsWhen Rukmini stood in Delhi, answering questions about her embroidery, she was not just representing herself. She carried with her generations of unnamed women who stitched without recognition. Her journey—from Kalna to Kolkata, from fear to flight, from anonymity to acknowledgement—mirrors a larger shift underway in India’s handloom sector. It is slow. It is uneven. But stitch by stitch, story by story, it is happening. And sometimes, it begins with a first flight.