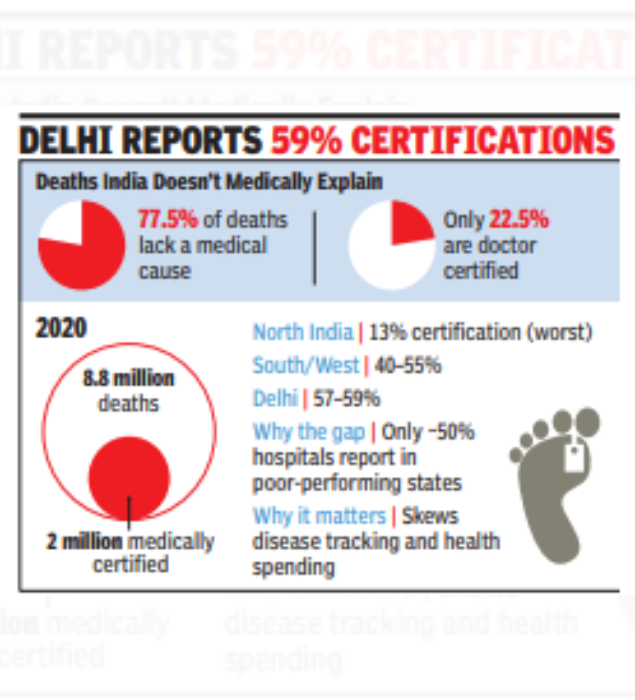

NEW DELHI: India records one of the highest numbers of deaths globally, yet the country still does not know what most people die of – a gap most pronounced in north India and even the national capital. A nationwide study published in Scientific Reports has found that only 22.5% of deaths in India are medically certified, leaving nearly four out of five deaths without a doctor-confirmed cause in official records. The findings are particularly significant for Delhi and north Indian states, which together account for a large share of the population. North India has the poorest medical certification of deaths, averaging just 13%, while Delhi’s rate has remained stagnant at around 57-59% for years – far from universal coverage despite its dense network of hospitals and medical colleges. The consequences extend well beyond record-keeping. “Without knowing the cause of death, it becomes difficult to assess disease prevalence nationally or regionally, which in turn affects health delivery, especially in remote areas,” said Dr Vinay Aggarwal, former national president of Indian Medical Association. He added that poor death documentation also affected processes such as electoral roll revision, underlining the wider administrative fallout.

Public health experts warn that unreliable cause-of-death data means govts are effectively planning health policy without knowing which diseases are killing people. Deaths from heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, infections, maternal causes, injuries and suicides cannot be accurately tracked, distorting disease burden estimates and skewing health spending. Weak certification also delays outbreak detection and undermines surveillance at a time when non-communicable diseases account for a growing share of adult deaths. The study tracked death certification patterns across India over 15 years, from 2006 to 2020. Regional disparities are stark. Large parts of north and east India continue to report single-digit or low double-digit certification rates, pulling down national averages and leaving millions of deaths each year without medical explanation. In contrast, southern and western states perform far better, reflecting stronger hospital reporting and administrative compliance. Some Union Territories are close to universal coverage – Lakshadweep reports over 94% medical certification, while Goa has near-complete coverage. The study challenges the assumption that doctor shortages alone explain the gap. While poorly performing states have fewer physicians, the strongest determinant is whether hospitals actually report deaths. In low-performing states, only about half of registered hospitals submit cause-of-death data, compared with over 90% reporting in high-performing states and UTs. The scale of the problem is stark. In 2020, India recorded around 8.8 million deaths. While about 80% were registered, only around 2 million had a medically certified cause. Progress has been slow, with certification improving by just 2.5 percentage points over a decade, despite expanded health infrastructure. Researchers warn that unless medical certification becomes routine and enforceable – particularly in north India and large urban centres like Delhi – India will continue to underestimate major killers, knowing far more about how many people die than why they die.