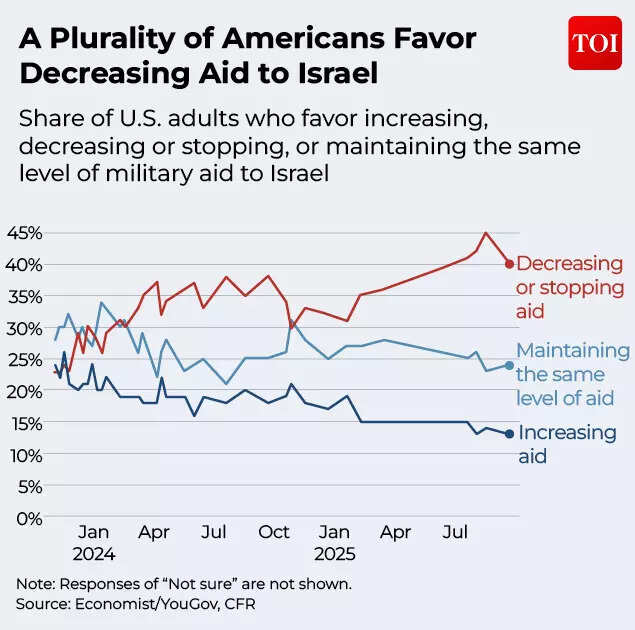

NEW DELHI: For decades, Israel has been one of the most heavily backed partners of the United States — militarily, diplomatically, and politically. From guaranteed military financing and preferential access to cutting-edge weapons, to routine diplomatic shielding at the United Nations, the US–Israel relationship has often appeared less like a conventional alliance and more like a protected arrangement.That is why Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s recent public assertion that Israel aims to taper US military aid “to zero” within a decade has raised eyebrows — not just in Washington, but across the Middle East and within Israel itself. Speaking to The Economist, Netanyahu framed the move as part of a long-term transition toward strategic self-reliance, even as the current 10-year US–Israel security framework remains in force until 2028.

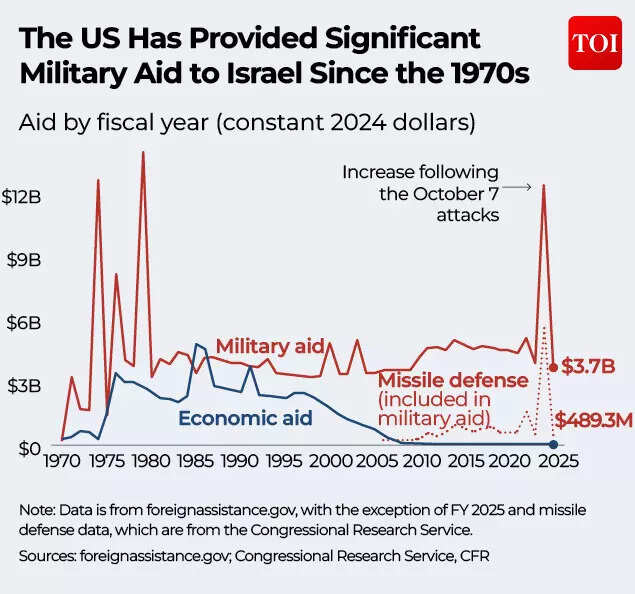

The statement comes at a moment when US involvement in Israel’s war decisions, ceasefire enforcement in Gaza, and crisis management with Iran has become unusually direct — prompting critics to describe Washington’s role as less that of an ally and more of a supervisor. At the same time, shifting public opinion inside the United States, especially among independents and younger voters, is forcing uncomfortable questions about whether Israel’s privileged position in American foreign policy is politically sustainable.So why has Israel historically depended deeply on the United States? Why has Washington treated Israel as a special case for nearly eight decades? And why is Netanyahu now signalling a desire to loosen that embrace?The answers lie in a layered mix of history, law, strategy, domestic politics, and institutional design — each reinforcing the other.From early recognition to strategic dependencyThe United States’ relationship with Israel did not begin as a military alliance, nor was it conceived as one. When President Harry Truman recognised the State of Israel in May 1948, the decision was driven as much by moral conviction and domestic political considerations as by strategic calculation. Washington, at the time, was cautious about being drawn into Middle Eastern conflicts and maintained an arms embargo on the region, including Israel. For nearly two decades after its founding, Israel survived largely without American weapons, turning instead to European suppliers, most notably France, to build its early military capabilities.The transformation of that political recognition into strategic dependency unfolded gradually, shaped by war and geopolitics rather than ideology alone. The 1967 Six-Day War altered regional power equations and heightened Washington’s interest in Israel as a stabilising force during the Cold War. But it was the 1973 Yom Kippur War that proved decisive. As Israel faced coordinated attacks from Egypt and Syria, the United States mounted a massive emergency resupply operation, signalling that Israel’s survival had become a core American interest. That moment embedded a lasting assumption in Israeli strategic thinking: in an existential crisis, US support would be indispensable.From the mid-1970s onward, American involvement shifted from episodic intervention to structural partnership. Military assistance expanded, first as loans and later as grants, while defence cooperation deepened across air power, intelligence sharing, and joint planning. By the time US military aid was converted fully into grants in the 1980s, Israel’s armed forces were increasingly built around American platforms and supply chains. What began as diplomatic recognition thus evolved into a tightly integrated security relationship — one that offered Israel unmatched military advantages, but also tied its long-term defence planning to Washington’s political will.How Israel became ‘dependent’ — by design, not weaknessAmerican military assistance to Israel is often portrayed as a subsidy — a steady transfer of US taxpayer money to support Israel’s defence. That framing misses the point. What Washington has constructed over decades is not a financial handout but a structured system that shapes how Israel equips its forces, plans wars, and sustains combat.At the core of this system is Foreign Military Financing (FMF). Israel does not receive cash. It receives US government credit that must be spent on American weapons, platforms, spares, and services. The money cycles back into the US defence industry while binding Israel to US aircraft, munitions, maintenance chains, and upgrade pipelines. Israel’s air force, missile defence, precision-guided weapons, and logistics architecture are now tightly integrated with American supply lines.Since the late 1990s, US aid has been governed by multi-year memoranda of understanding, not annual negotiations. The current 2016 MOU guarantees $3.8 billion annually through 2028, giving Israel rare long-term certainty for procurement and force modernisation. No other US partner receives this level of assured funding without a mutual defence treaty.

Israel also enjoys exceptional treatment within FMF. It receives its full annual allocation in a lump sum at the start of the fiscal year, rather than in monthly tranches. It is among the very few countries allowed to use FMF for direct commercial sales with US defence firms. Until recently, it could spend a portion of the aid domestically through offshore procurement — a provision that helped build Israel’s defence industry and is now being phased out.During major conflicts, Congress routinely approves supplemental aid on top of the MOU, particularly to replenish air-defence interceptors and precision munitions. Why Israel’s aid is differentUS military assistance to Israel stands apart not because of its size alone, but because of the privileges, predictability, and legal protections embedded in it. No other American partner combines all these features simultaneously.

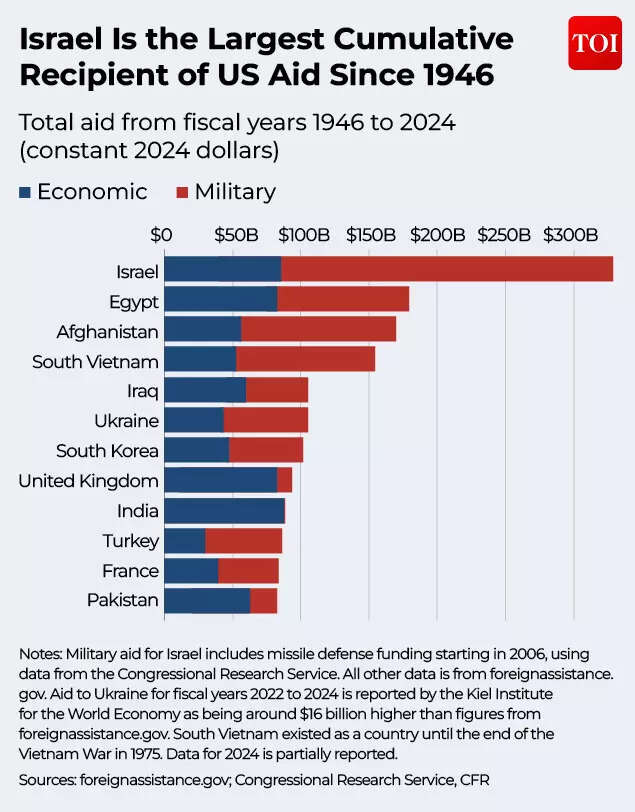

- First, Israel is the largest cumulative recipient of US foreign aid since World War II, having received over $300 billion in inflation-adjusted assistance, the overwhelming majority of it military. But unlike countries such as Egypt, Jordan, Ukraine, or Pakistan, Israel’s aid is governed almost entirely by long-term frameworks rather than annual bargaining. The current 2016 memorandum of understanding guarantees $3.8 billion every year through 2028, insulating Israel from congressional volatility that affects other recipients.

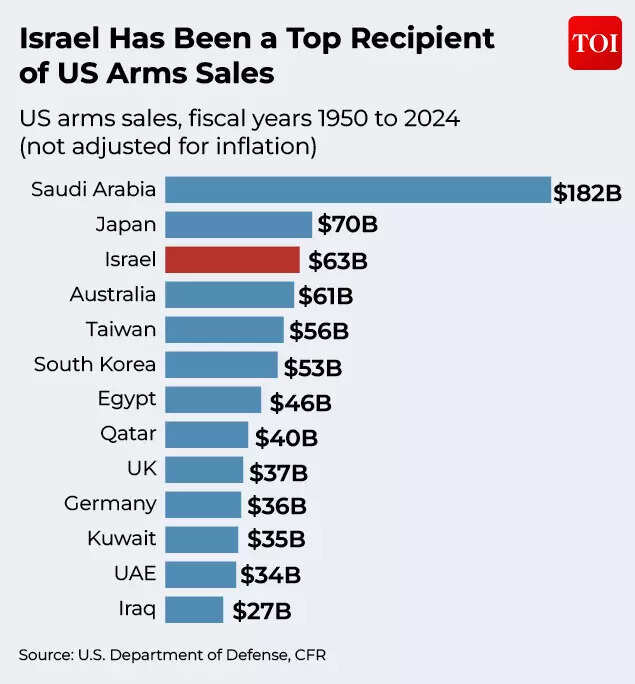

- Second, Israel enjoys unmatched flexibility within the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) programme. While most FMF recipients receive funds in monthly tranches and must procure weapons strictly through US government channels, Israel receives its entire annual allocation upfront in a lump sum and is permitted to make direct commercial purchases from US defence firms. This accelerates procurement timelines and allows Israel to negotiate directly with manufacturers — a privilege shared by very few countries.

- Third, Israel historically benefited from offshore procurement (OSP) — the ability to spend a portion of US aid inside its own defence industry. At its peak, this allowed Israel to allocate up to 25% of FMF domestically, helping build firms like Rafael and Elbit Systems. This exception is now being phased out under the current MOU, but no other US ally used American military aid as a tool of domestic industrial development to this extent.

- Fourth, Israel’s security advantage is protected by US law, not just policy. Since 2008, Washington has been legally required to preserve Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge (QME). This means the US must assess arms sales to Middle Eastern states to ensure they do not erode Israel’s military superiority — and if they do, Israel must be compensated with more advanced systems. No comparable legal obligation exists for any other US partner.

- Fifth, Israel benefits from routine wartime replenishment beyond baseline aid. During major conflicts, Congress has repeatedly approved supplemental appropriations — often running into billions of dollars — to restock missile interceptors, precision-guided munitions, and air-defence systems. These top-ups sit outside the MOU and reinforce the assumption that Israel’s military sustainability during war is a shared US responsibility.

- Sixth, Israel combines deep military assistance with exceptional diplomatic protection. The United States has repeatedly used its veto at the UN Security Council to block resolutions critical of Israel, including ceasefire demands. While other allies occasionally receive diplomatic backing, none benefit from such consistent shielding during active military operations.

Finally, Israel receives all these benefits without a mutual defence treaty. Unlike Nato allies, Japan, or South Korea, the US is not legally bound to fight on Israel’s behalf — yet Israel enjoys funding predictability, legal military guarantees, intelligence cooperation, and diplomatic cover that rival or exceed those treaty allies.The legal pillar: Israel’s military edge written into US lawIsrael’s exceptional status in US security policy rests on a legal doctrine known as the Qualitative Military Edge (QME). QME means that Israel must always possess superior military capability — technology, training, and firepower — over any regional adversary, even if those adversaries are larger in number.The concept emerged in the late 1960s, when the US abandoned its earlier policy of maintaining balance between Israel and Arab states and approved the sale of advanced F-4 Phantom fighter jets to Israel. Over time, this strategic preference hardened into law. In 2008, Congress codified QME through amendments to the US Arms Export Control Act, turning Israel’s military superiority from a policy choice into a statutory obligation.Under QME, the US government is legally required to assess whether proposed arms sales to Middle Eastern countries — including Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, or Qatar — could reduce Israel’s military advantage. If a sale is judged to affect Israel’s edge, Washington must either modify the deal, delay it, or compensate Israel with more advanced weapons, earlier access, or additional capabilities.

This requirement has shaped real outcomes. Israel has often received cutting-edge US systems ahead of other regional partners, from advanced combat aircraft to precision-guided munitions and missile-defence technologies. In several cases, US arms packages for Arab states have been adjusted or paired with parallel upgrades for Israel to preserve the mandated imbalance.No other US ally enjoys a similar legal guarantee. Israel’s advantage, by contrast, is written into US law, binding successive presidents regardless of party or political inclination.QME also institutionalises Israel’s influence within US decision-making. Israeli officials are formally consulted on major regional arms transfers, embedding Israel’s security concerns into American procurement and diplomacy. While this reduces uncertainty for Israel, it also limits Washington’s flexibility in managing relationships across the Middle East.QME converts US military aid from discretionary assistance into a legal commitment to preserve Israeli superiority. It explains why Israel’s support package functions less like foreign aid and more like a standing security guarantee — enforced not by treaty, but by American statute.Missile defence: The emotional core of the allianceIf military aid is the architecture of the US–Israel relationship, missile defence is its emotional centre. No other component of the alliance so effectively fuses strategic logic with moral justification, making it politically resilient across administrations and crises.Unlike fighter jets or offensive munitions, missile defence is framed almost exclusively as civilian protection. Systems such as Iron Dome, David’s Sling, Arrow, and the emerging Iron Beam are presented not as instruments of power projection but as shields against indiscriminate rocket and missile attacks. This framing has proven decisive in Washington, where funding defensive systems carries far lower political cost than supplying offensive weapons during active conflicts.Missile defence cooperation is also uniquely institutionalised. Under the current US–Israel MoU, $500 million annually is earmarked specifically for missile defence programmes. This funding is supplemented regularly during wartime. During the Gaza conflict, Congress approved additional billions of dollars to replenish interceptors, reflecting bipartisan consensus that Israel’s air-defence sustainability is a shared responsibility.

From a strategic standpoint, missile defence also serves American interests. US firms co-develop and manufacture key components, gaining access to combat-tested data and accelerating technological innovation in radar, intercept algorithms, and directed-energy systems. Joint projects allow the US military to observe how layered defences perform under sustained fire — data that no testing range can replicate.Politically, missile defence functions as a firewall. Even when debates rage over humanitarian impact, settlements, or ceasefires, funding for interceptors and radar systems is rarely questioned. In several congressional debates, support for missile defence has been explicitly separated from broader critiques of Israeli policy, allowing Washington to signal concern while maintaining core military backing.Diplomatic shielding: The UN veto patternBeyond military aid, the United States’ strongest support for Israel has been diplomatic, most visibly through its use of the UN Security Council veto. Since 1972, Washington has vetoed dozens of Israel-related resolutions, making Israel the most frequent beneficiary of the American veto.These vetoes have blocked resolutions calling for ceasefires, condemnation of Israeli military actions, scrutiny of settlement activity, and the creation of investigative mechanisms. Across administrations, the US has argued that such resolutions are one-sided, undermine negotiations, or fail to address actions by groups like Hamas.During the Gaza war, the pattern has intensified. The US repeatedly vetoed or stalled Security Council resolutions demanding an immediate ceasefire, instead pushing language centred on humanitarian pauses, hostage releases, and Israel’s right to self-defence.No other US ally receives this level of diplomatic protection. Even treaty allies face Security Council action without guaranteed US intervention. In Israel’s case, vetoes function as a strategic shield, preventing binding international constraints during active military operations and preserving Washington’s control over diplomatic timing.

The cost has been reputational. Repeated vetoes have deepened accusations of double standards and strained US ties with parts of Europe and the Global South. Yet successive administrations have judged this preferable to allowing the UN to shape Israel’s military conduct without American influence.In effect, the veto does not change the battlefield — it buys time, narrows consequences, and completes the system of exceptional support that underpins the US-Israel relationship.Trump and Netanyahu: From alignment to supervisionDonald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu began as unusually aligned partners. During Trump’s first term, Washington delivered a series of long-standing Israeli objectives: recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, and a peace plan drafted largely on Israeli terms. The relationship appeared ideological, personal, and unconditional.That alignment has since shifted into something more transactional and managerial. During the Gaza war and subsequent ceasefire efforts, the Trump administration moved from backing Israeli decisions to actively managing them. Senior US officials shuttled frequently to Israel, reversed Israeli moves on humanitarian aid, and intervened directly to enforce compliance with US-brokered ceasefire arrangements.This shift reflects Trump’s governing style rather than a break with Israel. Trump views foreign policy through outcomes and optics, not alliances. When Israeli actions threatened US interests — prolonging war, destabilising the region, or undercutting Trump’s claim to deal-making — Washington stepped in. Support remained, but autonomy narrowed.The result has been an inversion of roles. Israel retained military backing and diplomatic cover, but the United States assumed operational oversight in critical moments. Ceasefire terms, humanitarian access, and escalation thresholds increasingly required American approval.Netanyahu has rejected claims that Israel has become a client state. Yet the dynamic is clear: alignment gave way to supervision. Trump’s support remains strong, but it is conditional on control — turning the relationship from partnership into managed dependence, even as Netanyahu publicly argues for greater independence.